2.6 Sienese stories of famous people

Casanova makes no accomplishments

It was the evening of April 19, 1770, the city was gazing into a beautiful spring sunset. A carriage with its bellows lowered was seen passing through the Camollia gate. It carried a gentleman with an olive skin color, a pronounced profile, a penetrating gaze, very interested in observing what was happening next to him. This was Giacomo Casanova, who arrived in Siena for a few days of vacation. Waiting for him was the abbot Giuseppe Ciaccheri, librarian and vice-rector of the University, who would act as his guide during his stay in Siena.

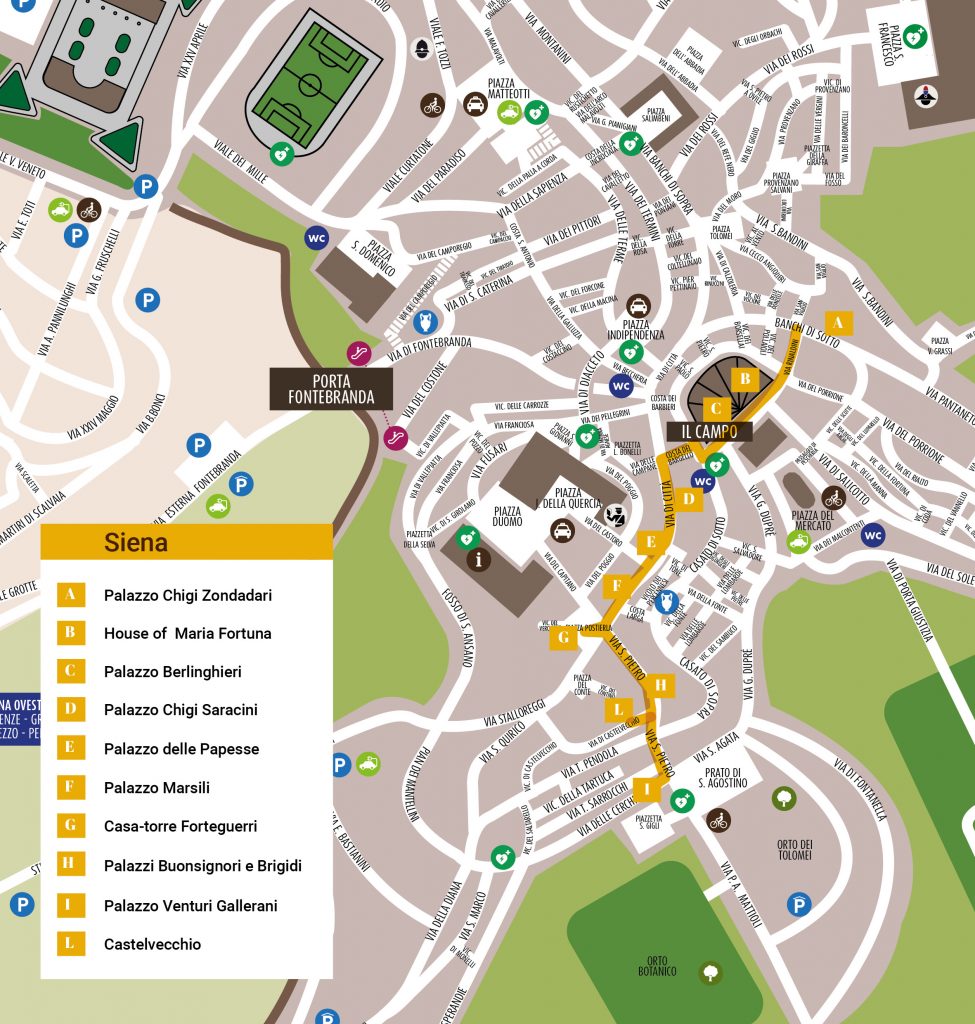

The chronicle of those days can be found in the Histoire de ma vie, an autobiographical work in which Casanova narrates (sometimes, imaginatively, he invents) events and misadventures of his own life. From these pages we learn that the Sienese meetings worthy of remembrance had been those with the Ciaccheri, the poetess Maria Fortuna, the Marquise Violante Chigi Zondadari. The latter lived in the family palace located at number 46 of Banchi di Sotto, an ancient palace rebuilt in 1724 on a project by Antonio Valeri. The Marchioness was also an animator of the Sienese salons, an easygoing woman with many interests. So Ciaccheri felt that Casanova should meet her. The meeting took place, therefore, at the Chigi Zondadari house.  In his memories, the Venetian notes that he was standing before a charming forty-seven-year-old widow (her husband Flavio had died the year before) who, though no longer young, still teased the senses. And, in fact, the incurable charmer immediately implemented his techniques of fascination. One can read about the courting strategies in Histoire. The two discuss their different approaches to life. Casanova says he is now devoted to carpe diem: «the freedom to enjoy only the moment is a grace granted to me by the god Apollo». The noblewoman does not think so, because «the pleasure that comes from desires and sometimes even from sighing is better, as it is infinitely more alive». Giacomo immediately understands that, in this case, the love business is not easy. However, he receives an invitation to lunch for the next day at the Marquise’s villa in Vicobello. Here again Violante displays charm and slight unscrupulousness. To the extent that Casanova will then have to admit to himself how, from the condition of seducer, he had suddenly found himself in that of seduced. To justify that temptation, he would say that the more years went by (he was 45 at the time), the more he was attracted not to matter, but to the spirit, to the intellect of women («The spirit became the medium through which my weakened senses needed to get moving»). Already the night before, leaving Palazzo Chigi Zondadari, Casanova had declared to Ciaccheri that, attracted by the marquise’s charm, the only woman he would have frequented during his stay in Siena would have been her, «and then what God would have liked would have happened». God did not like it and, presumably, Violante did not like it either, perhaps little convinced by his courtier’s arguments about the principle that «the greatest good of all is the one you enjoy» without useless waiting and dripping with desire. So it was a minor Casanova that Giacomo created in his Sienese days. No alcoves smelling of wheat and nobility, but only the rough sheets of the inn I Tre Re. From where he packed, even earlier than expected, to Rome. While travelling by carriage, he was travelling on the ancient Cassia, the image of the Marquise Violante, her vivacity and spontaneity, her grace in «knowing how to return a compliment as soon as the right hand was offered to her». No doubt: the seducer had been seduced.

In his memories, the Venetian notes that he was standing before a charming forty-seven-year-old widow (her husband Flavio had died the year before) who, though no longer young, still teased the senses. And, in fact, the incurable charmer immediately implemented his techniques of fascination. One can read about the courting strategies in Histoire. The two discuss their different approaches to life. Casanova says he is now devoted to carpe diem: «the freedom to enjoy only the moment is a grace granted to me by the god Apollo». The noblewoman does not think so, because «the pleasure that comes from desires and sometimes even from sighing is better, as it is infinitely more alive». Giacomo immediately understands that, in this case, the love business is not easy. However, he receives an invitation to lunch for the next day at the Marquise’s villa in Vicobello. Here again Violante displays charm and slight unscrupulousness. To the extent that Casanova will then have to admit to himself how, from the condition of seducer, he had suddenly found himself in that of seduced. To justify that temptation, he would say that the more years went by (he was 45 at the time), the more he was attracted not to matter, but to the spirit, to the intellect of women («The spirit became the medium through which my weakened senses needed to get moving»). Already the night before, leaving Palazzo Chigi Zondadari, Casanova had declared to Ciaccheri that, attracted by the marquise’s charm, the only woman he would have frequented during his stay in Siena would have been her, «and then what God would have liked would have happened». God did not like it and, presumably, Violante did not like it either, perhaps little convinced by his courtier’s arguments about the principle that «the greatest good of all is the one you enjoy» without useless waiting and dripping with desire. So it was a minor Casanova that Giacomo created in his Sienese days. No alcoves smelling of wheat and nobility, but only the rough sheets of the inn I Tre Re. From where he packed, even earlier than expected, to Rome. While travelling by carriage, he was travelling on the ancient Cassia, the image of the Marquise Violante, her vivacity and spontaneity, her grace in «knowing how to return a compliment as soon as the right hand was offered to her». No doubt: the seducer had been seduced.

Talented but ugly

Let’s rewind the tape for a moment. Following Casanova, we leave the home of the Marquis Violante and turn right on via Rinaldini to reach Piazza del Campo, from where one can also see the rear facade of Palazzo Chigi Zondadari. So we move a little to the chapel of the Public Palace.

The other visit Casanova tells about is to the poetess Maria Fortuna. She was not a noblewoman, but a simple bourgeois, daughter of Bargello (the police commissioner). The maiden had two prerogatives: an exaggerated ugliness, a great skill in composing verses. Casanova also noticed this, and in the afternoon, accompanied by Ciaccheri, he went to Casa Fortuna, a small building with entrance from Piazza del Campo (at No. 78), on the corner of Via Salicotto. In the modest family living room, Maria showed off her poetic skills by challenging Casanova, who, sincerely surprised by the girl’s talents, was not short on compliments. He could not do the same concerning the appearance of that creature, so sublime in the poetic practice, but of “repugnant” appearance. Considerations that, after leaving the Fortuna’s house, Casanova did not fail to express to Ciaccheri, running into a sensational gaffe. As the conversation continued it became clear that the abbot was hopelessly in love with the young poetess. Giacomo, in order not to further humiliate his lover with such ugliness, then appealed to his own wisdom and experience, concluding that … “sublata lucerna” (with the lamp turned off) the pleasure could always be obtained.

Giulia loves Henri

Passing along the Palazzo Pubblico, after the entrance to via Giovanni Dupré stands Palazzo Berlinghieri, whose name is somehow linked to that of Henri Beyle, alias Stendhal. It happened, in fact, that a certain Daniello Berlinghieri, minister of Tuscany in Paris, was the guardian of Giulia Rinieri De Rocchi, a beautiful and adventurous girl to the point of declaring herself in love with the already forty-year-old Beyle. But when Sthendal visited Berlinghieri to ask the beautiful Giulia for marriage, the guardian, sharply rejected the offer (he had other plans for his pupil and certainly not the one – he said – to marry her to a “deadbeat” man). Giulia, a determined woman of character, knew how to take revenge: she became Beyle’s lover. The two met repeatedly in Siena in the winter of 1832, and even after his marriage, the relationship continued until the death of the French writer. Giulia Rinieri’s traits can be seen in Mathilde de la Môle, one of the characters in the novel Il rosso e il nero. Just as it has not escaped to the more informed that, in another novel, Stendhalian, La Certosa di Parma, there is mention, at the end, of a Palazzo di Vignano (in literary fiction found on the banks of the Po) which alludes, without doubt, to the villa “il Palazzo” which belonged to the Berlinghieri family in Vignano, not far from Siena.

Passing along the Palazzo Pubblico, after the entrance to via Giovanni Dupré stands Palazzo Berlinghieri, whose name is somehow linked to that of Henri Beyle, alias Stendhal. It happened, in fact, that a certain Daniello Berlinghieri, minister of Tuscany in Paris, was the guardian of Giulia Rinieri De Rocchi, a beautiful and adventurous girl to the point of declaring herself in love with the already forty-year-old Beyle. But when Sthendal visited Berlinghieri to ask the beautiful Giulia for marriage, the guardian, sharply rejected the offer (he had other plans for his pupil and certainly not the one – he said – to marry her to a “deadbeat” man). Giulia, a determined woman of character, knew how to take revenge: she became Beyle’s lover. The two met repeatedly in Siena in the winter of 1832, and even after his marriage, the relationship continued until the death of the French writer. Giulia Rinieri’s traits can be seen in Mathilde de la Môle, one of the characters in the novel Il rosso e il nero. Just as it has not escaped to the more informed that, in another novel, Stendhalian, La Certosa di Parma, there is mention, at the end, of a Palazzo di Vignano (in literary fiction found on the banks of the Po) which alludes, without doubt, to the villa “il Palazzo” which belonged to the Berlinghieri family in Vignano, not far from Siena.

Galilees and the moon as seen from Siena

From Piazza del Campo, through the alley of the Bargello, we walk towards via di Città and turn left. Unforgettable for its facade that follows the curvature of the street, we see the elegant Palazzo Chigi Saracini in Sienese Gothic style (the entrance is at number 89). Built on the pre-existing Palazzo Marescotti (XII century), it had fourteenth-century enlargements and others in later centuries with Renaissance elements. It was in 1770, when the Chigi family bought it, that the facade was further extended and the 14th century style was restored. The chronicles narrate that from the tower, now broken, on September 4, 1260 a young drummer followed all the stages of the battle of Montaperti telling the people that had gathered down there. Almost like a radio report, which, in a hectic tone, he would say: «They have passed the Arbia, and come up from the side of the hill; they come up from the other side; cry out for mercy; now they are at hand with enemies, now they are at hand; the battle is great on each side; pray to God to give strength and help to the people of Siena». At number 126 we find the Palazzo delle Papesse, built by Caterina Piccolomini, sister of Pius II (hence the name “of the Papesse”). Perhaps designed by Bernardo Rossellino (architect trusted by the pontiff), the building was finished in 1495 with the intervention of Antonio Federighi and Urbano da Cortona. It was also the archbishop’s residence, and in 1633 hosted Galileo Galilei for about six months. Galilee’s heliocentric theories are well known. He had tried to explain to the intransigent judges of the Holy Office the idea of a God speaking both through the “book of Nature” and through the “book of Scripture”. Nothing could be done, he didn’t convince them. Thus, on the morning of June 22, 1633, Galilei was taken to a room in the convent of Santa Maria sopra Minerva in Rome and sentenced to prison. They also claimed that during the reading of the judgment he should kneel down and, beard on the ground, formally retract his mistake. The conviction included imprisonment in Rome, then turned into «confinement or border at the garden of the Trinità dei Monti», that is at the embassy of the Grand Duke of Tuscany. But after a few days, just because Ferdinand II was interested, the scientist was confined to Siena, in the house of Archbishop Ascanio Piccolomini.

Ascanio was born and raised in Florence, where his father had served as tutor to the son of the Grand Duke. His knowledge of Galilei as a mathematics teacher at the Grand Duke’s court dates back to his youth. After graduating, he was nominated Archbishop of Siena on 31 December 1628 and would remain there until he was transferred to Rome in 1671, the year of his death. He was a person of culture, open-minded, esteemed and affectionate towards Galilei. To the point that he tried to make his forced stay in the city of the Virgin as pleasant as possible. Archbishop Piccolomini lived in the palace with the same name, also known as the Palace of the Popes. Galileo arrived there on July 9. 1633 to stay there until December. The attentive hospitality of Ascanio calmed the discouragement of the scientist, restored his serenity, his desire to study and write. Later he would have entrusted to his friend Elia Diodati «[…] in Siena in the house of Monsig. Archbishop […] composed a treaty on a new subject, in matters of mechanics, full of many curious and useful speculations». He was referring to the speeches and mathematical demonstrations concerning two new sciences that would be published in Leiden in 1638. An unforgettable evening at Piccolomini’s house was that of August 1633, with the moon shining brightly and charmingly over the sky of Siena. After dark, a congregation of scholars, teachers and students climbed the archbishop’s stairs for an extraordinary astronomy lesson. Galilei, in fact, had had his “glasses” sent to him with which he had first observed the celestial bodies, and by placing the telescope on the roof-terrace of the palace he was able to offer the participants the emotion of a close encounter with the moon and stars.

Ascanio was born and raised in Florence, where his father had served as tutor to the son of the Grand Duke. His knowledge of Galilei as a mathematics teacher at the Grand Duke’s court dates back to his youth. After graduating, he was nominated Archbishop of Siena on 31 December 1628 and would remain there until he was transferred to Rome in 1671, the year of his death. He was a person of culture, open-minded, esteemed and affectionate towards Galilei. To the point that he tried to make his forced stay in the city of the Virgin as pleasant as possible. Archbishop Piccolomini lived in the palace with the same name, also known as the Palace of the Popes. Galileo arrived there on July 9. 1633 to stay there until December. The attentive hospitality of Ascanio calmed the discouragement of the scientist, restored his serenity, his desire to study and write. Later he would have entrusted to his friend Elia Diodati «[…] in Siena in the house of Monsig. Archbishop […] composed a treaty on a new subject, in matters of mechanics, full of many curious and useful speculations». He was referring to the speeches and mathematical demonstrations concerning two new sciences that would be published in Leiden in 1638. An unforgettable evening at Piccolomini’s house was that of August 1633, with the moon shining brightly and charmingly over the sky of Siena. After dark, a congregation of scholars, teachers and students climbed the archbishop’s stairs for an extraordinary astronomy lesson. Galilei, in fact, had had his “glasses” sent to him with which he had first observed the celestial bodies, and by placing the telescope on the roof-terrace of the palace he was able to offer the participants the emotion of a close encounter with the moon and stars. The Sienese Teofilo Gallaccini, a professor of philosophy and medicine, was part of the company, but he had expanded his studies to astronomy, mechanics, mathematics and architecture. Once sketched as well, he fixed the observations of the moon guided by Galileo in some tables, so as to leave evidence of what the Selenic night had revealed. Galileo’s forced stay with his archbishop friend ended on the following December 19, when the heretic was authorized to move to Arcetri, to an annex of the convent where his daughters Virginia and Livia were nuns. There, in a state of supervised residence, he would die in 1642 at the age of 78. Bertolt Brecht, in the play Galileo’s Life, which is largely based on the inquisition’s case against the scientist, at one point makes Galilei say: «In Siena, when I was young, I once saw some builders discussing for a few minutes how to move blocks of granite: after that, they abandoned a thousand- year-old method to adopt a new, simpler arrangement of ropes. At that moment I realized that the ancient age was over and the new age was beginning».

The Sienese Teofilo Gallaccini, a professor of philosophy and medicine, was part of the company, but he had expanded his studies to astronomy, mechanics, mathematics and architecture. Once sketched as well, he fixed the observations of the moon guided by Galileo in some tables, so as to leave evidence of what the Selenic night had revealed. Galileo’s forced stay with his archbishop friend ended on the following December 19, when the heretic was authorized to move to Arcetri, to an annex of the convent where his daughters Virginia and Livia were nuns. There, in a state of supervised residence, he would die in 1642 at the age of 78. Bertolt Brecht, in the play Galileo’s Life, which is largely based on the inquisition’s case against the scientist, at one point makes Galilei say: «In Siena, when I was young, I once saw some builders discussing for a few minutes how to move blocks of granite: after that, they abandoned a thousand- year-old method to adopt a new, simpler arrangement of ropes. At that moment I realized that the ancient age was over and the new age was beginning».

Rossellana kidnapped by pirates

Also in via di Città, beyond the junction of via del Castoro, at number 132 stands Palazzo Marsili with its gothic facade designed in 1444 by Luca di Bartolo Luponi, then remodelled in the 19th century. Here echoes a story worthy of The Thousand and One Nights. The story of Margherita Marsili, the “scarlet beauty”, so named for her red hair. It was April 1543. Margherita, still not even sixteen years old, was in Collecchio, in the family castle situated on the Maremma coast. The austere rooms allowed in the warmth of spring. The young girl, beautiful and already shaped like a woman, watched from the window the sea curve on the line of the horizon, but suddenly she noticed the approach of small boats in all the same as those that Father Nanni had one day referred to as ships of Saracen pirates, which raged more and more frequently on the coasts of the Maremma, raiding, ravaging, kidnapping boys who were sold as slaves on the eastern markets or girls destined for the harems of the powerful. They were headed by Khair-el-Din called the Barbarossa. Margherita unfortunately had seen right. To the point that it all happened in an awfully short time. The ugly guys were already hopping on the shore with clear intentions, and shortly afterwards they broke into the castle grabbing as much as they could and, in the despair of their parents and family, dragging the young scarlet beauty away. Barbarossa immediately noticed that a beauty like Margherita’s wasn’t something for rude pirates. It was better to make a profit by selling her to the Gran Visir, who was looking for light skinned maidens of rare graces for his harem. So it happened and the scarlet Margherita found herself in Turkey among the slaves of Suleiman II.  In the course of one night the young Sienese woman asked herself (and immediately resolved) a question: despair or manage the situation as best she could? She opted for the second hypothesis, and thanks to her obvious and hidden talents (in any case superior to those of her colleagues in misfortune) in a few weeks she tricked Suleiman to the point of becoming his favorite. But the girl had clear ideas and long-term plans. Thus, considering how the sultan had completely lost his mind for her, she was freed from her condition as a slave and got married as the only and exclusive wife (in a polygamic culture a real scandal!). From that wedding five children were born, and to ensure a future for ‘his’ child, the clever scarlet beauty set up tricks and even criminal acts, so as to kill the stepson Mustafa, Suleiman’s favorite, whom he had had from another woman. She managed to turn father and son against each other, until the latter was sentenced to death for betrayal. Selim, Margherita ́s eldest son, was thus able to ascend the throne of the exterminated Ottoman empire undisturbed. His brothers settle in various positions of power. Apparently, Margherita Marsili, exhausted by pregnancies and the stress of her perverse designs, died at only 37 years of age. But he did not give Suleiman the satisfaction of being seen dead. He was out of the way before. Genealogy experts were able to establish that Pope Alexander VII (1599-1667), son of Laura Marsili and Fabio Chigi, would have been the great-grandson of the sultana Margherita. Fans of incredible stories are willing to bet all the gold of Constantinople on the veracity of the affair.

In the course of one night the young Sienese woman asked herself (and immediately resolved) a question: despair or manage the situation as best she could? She opted for the second hypothesis, and thanks to her obvious and hidden talents (in any case superior to those of her colleagues in misfortune) in a few weeks she tricked Suleiman to the point of becoming his favorite. But the girl had clear ideas and long-term plans. Thus, considering how the sultan had completely lost his mind for her, she was freed from her condition as a slave and got married as the only and exclusive wife (in a polygamic culture a real scandal!). From that wedding five children were born, and to ensure a future for ‘his’ child, the clever scarlet beauty set up tricks and even criminal acts, so as to kill the stepson Mustafa, Suleiman’s favorite, whom he had had from another woman. She managed to turn father and son against each other, until the latter was sentenced to death for betrayal. Selim, Margherita ́s eldest son, was thus able to ascend the throne of the exterminated Ottoman empire undisturbed. His brothers settle in various positions of power. Apparently, Margherita Marsili, exhausted by pregnancies and the stress of her perverse designs, died at only 37 years of age. But he did not give Suleiman the satisfaction of being seen dead. He was out of the way before. Genealogy experts were able to establish that Pope Alexander VII (1599-1667), son of Laura Marsili and Fabio Chigi, would have been the great-grandson of the sultana Margherita. Fans of incredible stories are willing to bet all the gold of Constantinople on the veracity of the affair.

The lady with the ermine

We continue along via di Città until the crossroads known as the Four Cantons, where the widening takes the name of Piazza Postierla. The name is probably due to the fact that here, in the 13th century walls, there was a small doorway, that is one of those little doors, hidden in the walls, used by the patrol guards to reach their posts or to enter and exit in case of danger. The square, at one time the crossroads of the main streets of the Third of the City, became an important and prestigious area. Not surprisingly, in the 15th and 16th centuries, it was the usual meeting place of the nobles. On April 24, 1536, Carlo V. was welcomed there. On that occasion a large wooden eagle was built, symbol of the Empire, with the inscription Praesidium libertatis oure. The emperor greatly appreciated the tribute, to the extent that he granted the district of L’Aquila the title of nobility. Still today the noble bird of prey presides over the square from the top of the baptismal font of the district, the work of sculptor Bruno Buracchini (1963). On the corner with Via di Città is the fortified tower-house Forteguerri. A chronicle of 1283 narrates that, in spite of the Incontri family, living in the nearby via di Stalloreggi, the Forteguerri family had built the overpass that joined their tower to the facing Palazzo Borghesi (rebuilt in 1513- 14), so as to control and disturb the passage of the hated neighbors. We continue along via di San Pietro. At number 29 one can find the National Art Gallery, which is worth a visit to see, in a unique collection, the evolutionary process of Sienese painting from the end of the 12th century to the first half of the 17th century. The Museum is located in the palaces Buonsignori and Brigidi. The first building dates back to the fifteenth century, although, following the nineteenth-century restorations, the facade looks very similar to the Palazzo Pubblico.  Of earlier construction (14th century) is the Palazzo Brigidi, with which we come across the legend of Pia de’ Tolomei, since this was the residence of Nel Pannocchieschi, allegedly Pia’s not exactly exemplary groom. In the palace there is a spiral staircase, called “della Pia”. But it’s time to move on to another story. We do this by walking all the way along Via San Pietro and, when we reach the Porta all’Arco, turning into Via delle Cerchia (also in this case the name refers to the ancient circle of walls of the 13th century where the Porta all’Arco was opened). In the city of noble houses, sometimes a name is enough to open pages of history. It can also happen passing through this street, where at number 5 is located the venturi Gallerani palace. A lineage to which Cecilia (daughter of Fazio Gallerani and Margherita de’ Busti) also belonged, the one who was portrayed by Leonardo in the celebrated painting La dama con l’ermellino. So let’s see if we can reconstruct the Gallerani story. Cecilia’s family had emigrated to Milan in the early 1400s. The girl’s grandfather, Sigerio, a lawyer and a convinced supporter of the Ghibelline party, had been forced to change his mind because Siena was becoming unbreathable because of the increasingly popular Guelfism. In the Viscountess capital he began to work as a civil servant, a career then continued by his son Bartholomew. Just for the entry of his nephew Bartolomeo, the doors of the Ducal Palace could also open to Fazio (Cecilia’s father) who introduced him to the court of Bianca Maria, the now widow of Francesco Sforza. Having become correspondents at the ducal court, the Gallerans guaranteed themselves a good standard of living; at least until Fazio’s death, which marked the beginning of objective economic difficulties. Cecilia’s mother, an educated woman, however, did not neglect the education of the girl, the penultimate of eight children, who showed a remarkable aptitude for studies. In 1483, when the little girl was ten years old, a marriage agreement had been made between Cecilia and Stefano Visconti, in order to avoid her ending up in a convent, a fate common to all girls who had not found a husband. It happened, however, that the agreement lapsed, as the Gallerani family found itself unable to guarantee the agreed endowment. As the years go by, Cecilia is sixteen, and given the family’s continuing financial problems, she takes pen and paper and files a petition with the court asking for the return of the confiscated lands, already owned by her father. In the document, dated 1489, it appears that the sixteen-year-old girl did not live with her brothers, but in a house of her own; and that to continue her studies she had absolutely no need to take refuge in a convent. In short, someone was supporting her, and we also know who: Cecilia’s graces had made Ludovico il Moro lose his head, a hillbilly man but sensitive to feminine charm. The young Gallerani had become his mistress, although the wedding between Moro and Beatrice d’Este was announced. The relationship between them is certified by an explicit letter, dated November 8, 1490, in which Giacomo Trotti, Estensi ambassador to the court of the Sforza family, wrote concerned to the Duke of Ferrara, expressing some doubt as to whether Moro wished to have “the madonna duchessa nostra” (that os Beatrice d’Este) at his feet, because lord Ludovico seemed completely fallen in love with «that girlfriend of his who keeps him in a castle and to whom he wishes all his good and is as pregnant and beautiful as a flower». According to Trotti, that infatuation was a real disease for the Duke, just to see how he had physically weakened. On the other hand, to come to the artistic aspects that made Cecilia famous and immortal, it should be remembered that Leonardo, in those years, was in Milan at the service of Ludovico il Moro.

Of earlier construction (14th century) is the Palazzo Brigidi, with which we come across the legend of Pia de’ Tolomei, since this was the residence of Nel Pannocchieschi, allegedly Pia’s not exactly exemplary groom. In the palace there is a spiral staircase, called “della Pia”. But it’s time to move on to another story. We do this by walking all the way along Via San Pietro and, when we reach the Porta all’Arco, turning into Via delle Cerchia (also in this case the name refers to the ancient circle of walls of the 13th century where the Porta all’Arco was opened). In the city of noble houses, sometimes a name is enough to open pages of history. It can also happen passing through this street, where at number 5 is located the venturi Gallerani palace. A lineage to which Cecilia (daughter of Fazio Gallerani and Margherita de’ Busti) also belonged, the one who was portrayed by Leonardo in the celebrated painting La dama con l’ermellino. So let’s see if we can reconstruct the Gallerani story. Cecilia’s family had emigrated to Milan in the early 1400s. The girl’s grandfather, Sigerio, a lawyer and a convinced supporter of the Ghibelline party, had been forced to change his mind because Siena was becoming unbreathable because of the increasingly popular Guelfism. In the Viscountess capital he began to work as a civil servant, a career then continued by his son Bartholomew. Just for the entry of his nephew Bartolomeo, the doors of the Ducal Palace could also open to Fazio (Cecilia’s father) who introduced him to the court of Bianca Maria, the now widow of Francesco Sforza. Having become correspondents at the ducal court, the Gallerans guaranteed themselves a good standard of living; at least until Fazio’s death, which marked the beginning of objective economic difficulties. Cecilia’s mother, an educated woman, however, did not neglect the education of the girl, the penultimate of eight children, who showed a remarkable aptitude for studies. In 1483, when the little girl was ten years old, a marriage agreement had been made between Cecilia and Stefano Visconti, in order to avoid her ending up in a convent, a fate common to all girls who had not found a husband. It happened, however, that the agreement lapsed, as the Gallerani family found itself unable to guarantee the agreed endowment. As the years go by, Cecilia is sixteen, and given the family’s continuing financial problems, she takes pen and paper and files a petition with the court asking for the return of the confiscated lands, already owned by her father. In the document, dated 1489, it appears that the sixteen-year-old girl did not live with her brothers, but in a house of her own; and that to continue her studies she had absolutely no need to take refuge in a convent. In short, someone was supporting her, and we also know who: Cecilia’s graces had made Ludovico il Moro lose his head, a hillbilly man but sensitive to feminine charm. The young Gallerani had become his mistress, although the wedding between Moro and Beatrice d’Este was announced. The relationship between them is certified by an explicit letter, dated November 8, 1490, in which Giacomo Trotti, Estensi ambassador to the court of the Sforza family, wrote concerned to the Duke of Ferrara, expressing some doubt as to whether Moro wished to have “the madonna duchessa nostra” (that os Beatrice d’Este) at his feet, because lord Ludovico seemed completely fallen in love with «that girlfriend of his who keeps him in a castle and to whom he wishes all his good and is as pregnant and beautiful as a flower». According to Trotti, that infatuation was a real disease for the Duke, just to see how he had physically weakened. On the other hand, to come to the artistic aspects that made Cecilia famous and immortal, it should be remembered that Leonardo, in those years, was in Milan at the service of Ludovico il Moro. He had just finished La Vergine delle rocce, when the Duke (we are in that fateful 1489) commissioned him the portrait of Cecilia Gallerani. Thus was born what the history of art defines as the first modern portrait, since it introduced “the motions of the soul” into painting. Despite her young age, she shows a conscious, proud, intelligent look. Its oval is perfect, her eyes are intense. The hairstyle is already that of a woman (a lady), just like the dress and necklace she wears. A frontal light highlights the shoulders and that beautiful hand (also adult, confident) that barely touches the ermine, the heraldic symbol of the Sforza and (with a good dose of courtly hypocrisy) a metaphor of purity and moderation. Moreover, in the Greek language, ermine is said to be gallé: there is therefore also an allusion to Cecilia’s surname. The light, from her forehead and eyes, barely turns towards her nose and cheeks and then softens on her lips that seem to suggest a smile towards someone who is probably watching her. Cecilia Gallerani’s charm and personality had not gone unnoticed in ducal Milan, to the extent that she became friends with writers, artists and musicians. Matteo Bandello dedicated two novels to her and she was appreciated as the author of compositions in Latin and Italian. She remained at the Sforza court even after Ludovico’s marriage to Beatrice d’Este. She was removed when her little son Cesare was born, whose father was undoubtedly il Moro. She had a kind of good fortune by receiving houses and other goods as a gift. These included the palace of Via Broletto which became a meeting place for writers and high society figures.

He had just finished La Vergine delle rocce, when the Duke (we are in that fateful 1489) commissioned him the portrait of Cecilia Gallerani. Thus was born what the history of art defines as the first modern portrait, since it introduced “the motions of the soul” into painting. Despite her young age, she shows a conscious, proud, intelligent look. Its oval is perfect, her eyes are intense. The hairstyle is already that of a woman (a lady), just like the dress and necklace she wears. A frontal light highlights the shoulders and that beautiful hand (also adult, confident) that barely touches the ermine, the heraldic symbol of the Sforza and (with a good dose of courtly hypocrisy) a metaphor of purity and moderation. Moreover, in the Greek language, ermine is said to be gallé: there is therefore also an allusion to Cecilia’s surname. The light, from her forehead and eyes, barely turns towards her nose and cheeks and then softens on her lips that seem to suggest a smile towards someone who is probably watching her. Cecilia Gallerani’s charm and personality had not gone unnoticed in ducal Milan, to the extent that she became friends with writers, artists and musicians. Matteo Bandello dedicated two novels to her and she was appreciated as the author of compositions in Latin and Italian. She remained at the Sforza court even after Ludovico’s marriage to Beatrice d’Este. She was removed when her little son Cesare was born, whose father was undoubtedly il Moro. She had a kind of good fortune by receiving houses and other goods as a gift. These included the palace of Via Broletto which became a meeting place for writers and high society figures.

In July 1492 Cecilia married Count Ludwig Carminati. At the castle belonging to her husband, in San Giovanni in Croce (in the Cremonese area), she continued to animate meetings between artists, poets and writers. She died at the age of 63. But, as we mentioned, Cecilia is remembered perpetually thanks to Leonardo’s painting. That portrait was already a myth at the end of the fifteenth century: the court poet Bernardo Bellincioni dedicated the sonnet Above the portrait of Madonna Cecilia, which Leonardo did, in which he imagines a dialogue between the author and the envious Nature: «What are you angry about? To those who envy you have Nature / To Vinci who has portrayed one of your stars: / Cecilia! So beautiful today is the one / who in her beautiful eyes the sun seems a dark shadow» Over the centuries, The lady with the ermine did not have an easy life. Subjected to transfers from one place to another (Mantua, Krakow, Paris and then definitively Krakow), continuously under observation, even x-rayed, because – this is the reason for the many attentions – under the dark background that surrounds her there seems to be a landscape similar to that of Mona Lisa. And, if so, was this a rethinking of Leonardo or a subsequent intervention by someone else? Beyond the assumptions and academic disputes, Cecilia continues to stand there, in that mysterious darkness from which all her magnetic beauty comes out. At the end of this journey which has taken us through centuries, stories, lives that are not ordinary at all, we cannot fail to visit the oldest part of the city of Siena. We do this by walking backwards along via San Pietro, until, on the left, we find via Castelvecchio leading to what is believed to be the first fortified settlement of the city (11th century). This was the Castellum vetus (Castelvecchio) built strategically on the highest hill, protected by walls and structured just like a square-shaped fortification, with towers, a courtyard, interior paths. What remains of it can be seen when we walk up the hill and, therefore, the alley on the right which, through two large arches, leads to a nucleus of fortified houses gathered around a courtyard.

Produced by: toscanalibri.it

Texts edited by: Luigi Oliveto

Editorial coordination: Elisa Boniello e Laura Modafferi

Photos: Archivio Comune di Siena

Graphic design: Michela Bracciali