2.9 During the Risorgimento period

Long live the king

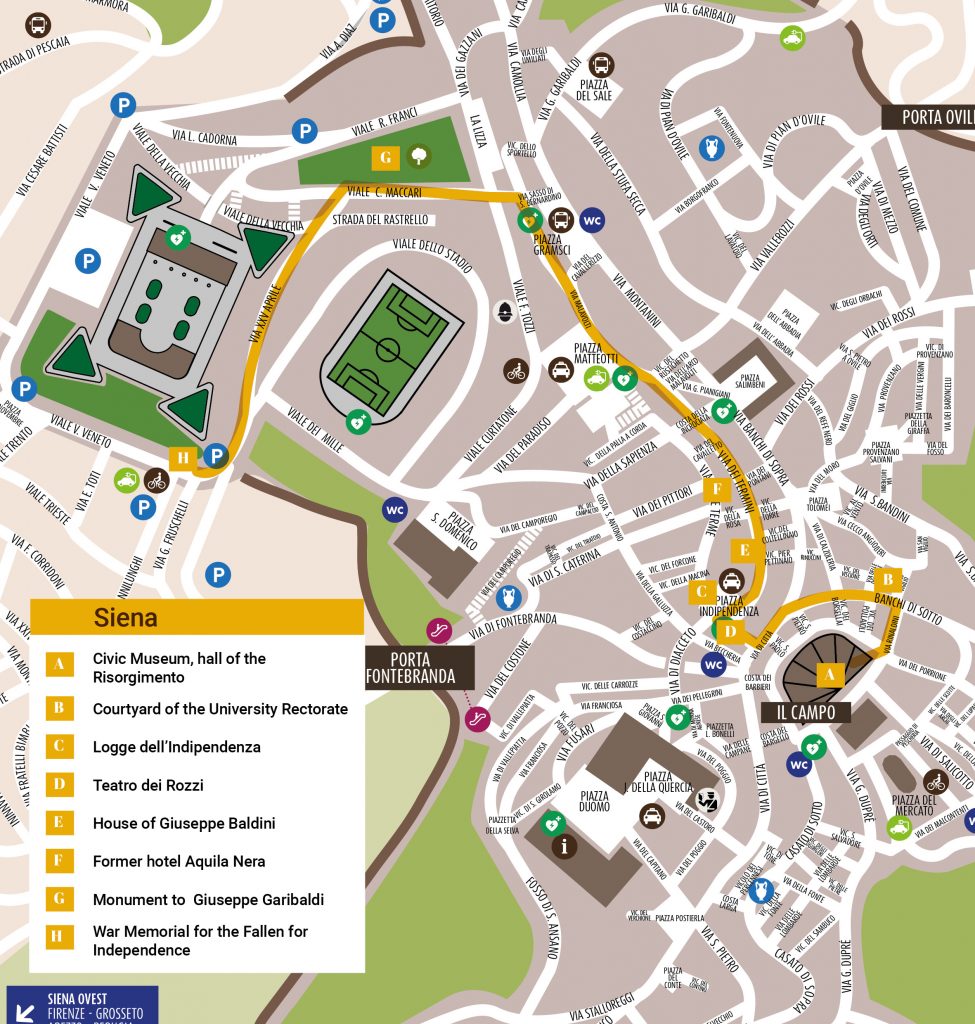

Our itinerary through Risorgimento Siena begins in Piazza del Campo, the heart of the city, which has always been the scene of major events and a symbol of civic passion.

In the mid-nineteenth century Siena had just over 32,000 inhabitants. The city was all set within the circle of the ancient walls, guarded at their gates by the customs guards. But not so much as to prevent the entry of new ideas that were disturbing the sleep of those who considered the Unification of Italy a mere bump in the road, hoping for a prompt restoration of the Grand Duchy of Tuscany and, above all, of the temporal power of the Church.

In Siena, liberal ideas had taken root. In 1830, when Giuseppe Mazzini had visited the city, several tricolour handkerchiefs had been confiscated—the central government had strictly forbidden their distribution. There was an increase in affiliates of Giovine Italia, so much so that in a concerned report by the government delegate it was stated that most schoolchildren were “imbued with modern maxims”. Mazzini himself noted, in August 1833, that «the Sienese are organised from head to toe and are susceptible of being incited to act». Siena was, therefore, a patriotic city of the first hour.

It is no wonder, then, that after the death of Vittorio Emanuele II in 1878, the mayor Luciano Banchi (from a young age a fervent supporter of the ideals of the Risorgimento) proposed to honour the first Italian sovereign by dedicating a space in the Palazzo Pubblico to him and naming Piazza del Campo after him; the square was known as Piazza Vittorio Emanuele II for the entire monarchical period. The project involved the pictorial decoration of an entire hall of the palace. Luigi Mussini, also a staunch patriot and authoritative director of the Art Institute of Siena, was called upon to coordinate the work. Mussini hired the best Sienese artists and—even though the artistic results were not always excellent—a cycle of frescoes was produced, which is now visible in the so-called Sala del Risorgimento, inaugurated in 1890.

So, let’s delve into this slice of 19th-century history. Here is the sequence of the frescoes. The meeting at Vignale (painted by Pietro Aldi): this recalls the armistice, signed on March 24, 1849 by Vittorio Emanuele II and the Austrian general, Radetsky, which ended the first Italian war of independence with the abdication of the King of Sardinia Carlo Alberto, in favour of his son Vittorio Emanuele II. The Battle of Palestro (Amos Cassioli): an episode from the Second War of Independence (31 May 1859) which saw the retreat of the Austrian troops, allowing Napoleon III to manoeuvre towards Milan. The Battle of S. Martino (Cassioli), which brought the Second War of Independence to an end on 24 June 1859 (in the consequent Treaty of Zurich, the Habsburgs would cede Lombardy to France, which assigned it to the Savoys, while Austria kept the Veneto together with the fortresses of Mantua and Peschiera). The meeting at Teano (Cassioli), which took place on 26 October 1860 between Vittorio Emanuele II and Giuseppe Garibaldi at the conclusion of the Expedition of the Thousand. Vittorio Emanuele II receives the plebiscite of the Romans (Cesare Maccari): on October 9, 1870, a few days after the taking of Rome, Vittorio Emanuele II received the plebiscite of the Romans in Florence (then capital of Italy). The transportation of the remains of Vittorio Emanuele II to the Pantheon (Maccari) took place on 17 January 1878. The frescoes on the ceiling depict The allegory of free Italy and the Regions that made up the newly-created Italian State.

In the same room there are also several sculptures by nineteenth-century Sienese artists (Giovanni Dupré, Tito Sarrocchi, and Enea Becheroni). Above them all stands the Tristitia by Emilio Gallori, presented at the Universal Exhibition of Paris in 1900, where it was awarded a gold medal. Gallori, who was very active in Rome, also created the Monument to Giuseppe Garibaldi on the Janiculum hill.

Two display cases contain relics from the Risorgimento. There is the uniform worn by the king in the battle of San Martino, which he himself had donated to Luigi Mussini to thank him for a portrait he had painted. In the second case is the photo, the red shirt and some other of Garibaldi’s objects that belonged to Luciano Raveggi (a Sienese native of Orbetello), who had participated in the Expedition of the Thousand.

A question of colours

We are now in Piazza del Campo, and we must not neglect to mention the events of the Palio, which in the nineteenth century were inevitably affected by political events. To reiterate the positions that opposed liberals to reactionaries, even colours and symbols of the contrade (districts) were taken as an excuse. The contrada of the Goose, for example, with its white, red and green, was considered against the Lorraines, and full of troublemakers who supported national unity. When they entered the square, the Tartuca (Tortoise) and Aquila (Eagle) banners were regularly booed, as the yellow and black colours (in the case of the Eagle also with the coat of arms) recalled the odious Austrian flag. In 1847 the Tartuca contrada tried to find a solution by replacing black with white, and thus entered into the sympathies of Pope Pius IX. But in 1848, after the victory of the Austrians at the Battle of Novara, the banner became yellow and black once again. So, boos were heard in the square again; eventually, in 1849, the contrada became resigned to changing the colours to yellow and turquoise.

There are several lively anecdotes on the subject. It is said that at the extraordinary Palio of 21 October 1849, attended by Leopold II, the standard-bearer of the Goose contrada, at the end of the flag-waving, had thrown his banner in such a sensational way that the Grand Duke was forced to raise his head up first and then to bow it to follow the return of the banner into the standard-bearer’s hand. Essentially—as malicious people remarked—he had been forced to bow to the tricolour flag, symbolised in the goose contrada’s colours.

Another episode on the subject is recounted by Mario Pratesi (a Tuscan writer who was very attached to the Risorgimento tradition) when he reported the presence of Massimo D’Azeglio at the Palio on 4 July 1858. According to Pratesi, the arrival of D’Azeglio greatly excited the Sienese liberals. Almost as if it meant “the announcement that it was the last hour for the Lorraine dynasty and for German”. As Pratesi wrote: «From the restoration of 1949 onwards, the Palio, even with the German bayonets that garrisoned the Republican square, served as a means of opening the hearts of the Italians: it was a breath of ancient freedom under servitude». In this climate of great excitement, the Goose won, despite having a horse that «would only become lively in races by being sprinkled with brandy and flooded with live eels». The white, red and green triumph further excited the people, and D’Azeglio was glorified as if it were he, or rather his ideas, that had won.

There were still issues with colours and emblems when Garibaldi, in 1867, visited Siena and attended the Palio. In this case, the applause was wasted with the appearance of the Torre, which recalled the colour of Garibaldi’s shirts. On several occasions, the red-clothed standard bearers paid tribute to Garibaldi, who looked out from the terrace of the Circolo degli Uniti, and they were reciprocated with gestures of sympathy by the Hero of the Two Worlds. The Garibaldi supporters were very irritated when the race won by the Lupa, a contrada that bears the symbol of Rome in its coat of arms, the city which Garibaldi was aiming to win back. In drawing up his report, the Carabinieri major did not fail to note the repeated applause addressed to the red flag of the Torre, as well as the fact that the victory of the Lupa «cost the reactionaries [as those who, in fact, were the progressives,were called] a lot of money, while it wasn’t so much appreciated by the opposite party, who allude it to the triumph of the Romans». The next day Garibaldi received a delegation of the Lupa contrada inhabitants. The victorious jockey was given a photo of himself with the following dedication written on it: «To Mario Bernini, champion of the victorious Lupa, herald of the victory of Rome». The photo is kept in the museum of the Contrada, together with the prize banner conquered in the race.

It would be worth dedicating a whole chapter to the story of the feeling that characterised the relationship between the Savoy family and the contradas of Siena. The chronicles of the period amply documented King Umberto and Queen Margherita’s visit to Siena in July 1887. Due to the protracted parliamentary work in which the king was engaged, the Palio was moved from July 2 to July 16 so that the royal family could attend. They were given an enthusiastic welcome. The queen was honoured with a panforte [type of cake] created especially for her, with a less spicy flavour than the traditional gingerbread (the recipe would later produce the panforte Margherita). The day after the Palio, King Umberto and his wife went to visit several contradas, among which, of course, the white-red-green Oca.

The Savoy family returned to Siena at other times and Queen Margherita was able to grant her protectorate to various contradas. This link would prove to be decisive in legitimising them before certain civil servants, such as the prefects, who, on the other hand, did not look favourably upon these associations, which seemed to avoid the established authority. The many Savoy symbols, still visible today in the heraldry of the contradas, bear witness to this mutual sympathy: Cyprus roses, knots and daisies, Annunziata collars, the letters U and M, initials of the royal names.

Patriotic students

From Piazza del Campo, via dei Rinaldini, we reach Banchi di Sotto. Immediately opposite, at number 55, we find the building that houses the Rectorate of the University of Siena. In the middle of the courtyard is the monument to the fallen in the battle of Curtatone and Montanara.

In military jargon, they’re known as “encounter.” They happen when two armies in manoeuvre find themselves facing each other, and are therefore forced to clash in the open field. This happened on May 29, 1848, during the First War of Independence, in Curtatone and Montanara, in the province of Mantua, between the Austrians and the Tuscan volunteers. The latter opposed resistance, allowing the Piedmontese to prepare for the clash that would take place the next day in Goito, where the Austrian army was beaten.

This was the situation in Tuscany at the time. Despite the discontent of the Austrians, Grand Duke Leopold II (in the wake of the first concessions made by Pius IX in the Papal States) could not help but implement the first reforms, such as a certain freedom of the press, the establishment of a state council and a National Guard. In the same way, he could not prevent a few thousand men from leaving for Lombardy, for the first War of Independence. Among them there were also groups of students from the University of Siena and Pisa. Fifty-five students and five teachers came from the Sienese Athenaeum. Two students lost their lives, and two others were taken prisoner. The event aroused emotion and feelings that have long remained alive in the city’s memory, so much so that on 29 May 1893, on the anniversary of the battle, the monument to the Fallen that we see in the courtyard of the Rectorate was inaugurated. It was created by the sculptor Raffaello Romanelli, and the base bears the phrase: Exoriare aliquis nostris ex ossibus ultor [«may one day, from my ashes, an avenger be born»]. These are the words that Dido pronounces in the Aeneid when, abandoned by Aeneas, she throws herself onto the pyre.

In the historical archive of the University (which can be visited using the entrance from the Rectorate’s courtyard) is the tricolour flag of the Sienese University Guard: it bears the Lorraine coat of arms on the obverse and the inscription Guardia universitaria on the reverse. Also on display is the uniform worn in the battle by the Sienese Carlo Corradino Chigi, head of the General Staff of the Tuscan troops, who was wounded at Curtatone and Montanara.

In the historical archive of the University (which can be visited using the entrance from the Rectorate’s courtyard) is the tricolour flag of the Sienese University Guard: it bears the Lorraine coat of arms on the obverse and the inscription Guardia universitaria on the reverse. Also on display is the uniform worn in the battle by the Sienese Carlo Corradino Chigi, head of the General Staff of the Tuscan troops, who was wounded at Curtatone and Montanara.

In memory of Independence

Leaving the courtyard of the University, we continue, on the right, along Banchi di Sotto, via di Città, until we find, also on the right, via delle Terme and then Piazza dell’Indipendenza.

The square took on its present appearance in 1887, when, according to Archimede Vestri’s design, a three-arched loggia was erected, leaning against Palazzo Ballati, whose medieval tower rises from the back of the loggia. The square then acquired a greater characterisation with the Monument to the Fallen for Italian Independence, the work of Tito Sarrocchi, which was inaugurated on September 20, 1879 and placed in front of the loggias that gave its presence an additional air of solemnity. It was then that the square was given the name of Independence, replacing the old place-name of Piazza San Pellegrino (such was the name of the now demolished church, which stood in this space). In 1958 the monument was improperly moved to the San Prospero district (we will have the opportunity to talk about this at the end of our itinerary).

The Teatro dei Rozzi can also be found in this square; the theatre was built in 1816 to a design by Alessandro Doveri, and extended in 1874. The ancient Accademia dei Rozzi, founded in 1531, was a place where illustrious guests often feasted when they came to Siena. This was also the case during Giuseppe Garibaldi’s stay in Siena in August 1867. On the evening of his arrival (Sunday, August 11) a banquet was organised at the Rozzi, which remained famous in Garibaldi’s history for a sort of ciphered message that resonated among those present. The official greeting was given by Professor Giuseppe Stocchi, who, believing he was interpreting Garibaldi’s vision, had just said that «we should go to Rome when the time is ripe». But the General, believing that there was no better time than now to carry out the enterprise of Rome, took the floor and pronounced the cryptic phrase: «we will move when things are fresh», that is, in the next autumn season. That mysterious expression became the watchword.

The Rozzi’s canteens were also set up for a banquet on the occasion of Giosuè Carducci’s visit in 1894. Indeed, from the pages of the Libero Cittadino of June 7, 1894 we learn that «eminent men by degree of culture, admirers, professors of the university and high school of Siena, offered the great poet a banquet in the buffet room of the Accademia dei Rozzi» . The testimonies of the time inform us that «although he already felt tired, nevertheless he still appeared powerful, and the great lion’s head stood proudly on his mighty shoulders, marked by proud austerity like a landscape of the Apuan Alps» . The poet, therefore, did not hold back, and to the many toasts that honoured him «he replied with one of those sculptural passages of prose, of which he alone possessed the secret of conceiving. He evoked the greatness of Republican Siena, asleep in the radiance of its glorious surrender, like Walkiria in the glow of the flame, waiting for the warrior genius of the homeland to awaken her at the first tremor of freedom. He alluded to his happy awakening with the demand for national independence and his phrases aroused such great enthusiasm that he brought the guests to an impressive, interminable ovation».

From the Black Eagle window

Following the roar of applause for the national Poet, we leave Piazza Indipendenza and move on to Via dei Termini. At number 19 we can just about read on a plaque corroded by time that «here lived Colonel Giuseppe Baldini, from Siena; of the immortal Garibaldi in the Expedition of the Thousand and in that of the Agro Romano, faithful and valiant follower; of the Unification of Italy, assertor and indefatigable supporter and advocate, ignited by the purest patriotism, reluctant to receive rewards and honours, he died honestly poor in Rome on June 2, 1893». Baldini, born in Siena in 1823, was known by the nickname of Ciaramella. He was an affiliate of Giovine Italia, and due to his political ideas he spent two years in prison, from 1852 to 1854. Later he set up a textile company. In 1860 Garibaldi entrusted him with the command of the Tiber Hunters Battalion in the capture of Orvieto and Montefiascone. He was wounded during a battle in the Agro Romano. The textile company went bankrupt, and Ciaramella went to seek its fortune in Egypt. After six years he returned to Italy, and in Rome he ended his days living on a modest war pension and the salary from his job as a rubbish collector.

During his time in Siena, Garibaldi did not fail to visit his dear friend Baldini, just as he met with other faithful followers. Among them was the commoner Baldovina Vestri, an exceptional character, born in Salicotto, in the contrada of the Torre. After a failed marriage, Vestri dedicated herself completely to Garibaldi’s cause. Following the clashes in Aspromonte, where the brothers Archimede and Ademaro had also fought, she sent Garibaldi a sum of money she had collected in support of the wounded. She followed her hero to the Agro Romano, and in the battle of Mentana she worked as a sutler, nurse, stablewoman, rifle reloader, and stretcher-bearer in the recovery of the dead and wounded. The letters that Garibaldi sent to her are kept in the Archives of the City of Siena. Archimedes was the creator of the Logge di Piazza Indipendenza project, which we mentioned earlier.

During his time in Siena, Garibaldi did not fail to visit his dear friend Baldini, just as he met with other faithful followers. Among them was the commoner Baldovina Vestri, an exceptional character, born in Salicotto, in the contrada of the Torre. After a failed marriage, Vestri dedicated herself completely to Garibaldi’s cause. Following the clashes in Aspromonte, where the brothers Archimede and Ademaro had also fought, she sent Garibaldi a sum of money she had collected in support of the wounded. She followed her hero to the Agro Romano, and in the battle of Mentana she worked as a sutler, nurse, stablewoman, rifle reloader, and stretcher-bearer in the recovery of the dead and wounded. The letters that Garibaldi sent to her are kept in the Archives of the City of Siena. Archimedes was the creator of the Logge di Piazza Indipendenza project, which we mentioned earlier.

From Via dei Termini we take the alley of Pier Pettinaio, which brings us to Banchi di Sopra. The Albergo Aquila Nera, where Garibaldi took lodging during his stay in the city, was located at the current number 29. It should be remembered that he had been asked to visit Siena jointly by the Società Operaia and the Fratellanza Militare. After several controversies about where the General should stay, he decided independently on the Black Eagle Hotel. Accompanied by his daughter Teresita and son-in-law Stefano Canzio, he arrived on the morning of August 11, at around ten o’clock, on the first train from Empoli, announced by the tolling of the city’s main bell. He was welcomed enthusiastically (although there were no local authorities in attendance), with a procession that, through Via Garibaldi (already bearing this name) accompanied his carriage to the Black Eagle, where a guard of honour was deployed.

Looking out from a window of the hotel, Garibaldi addressed the people for a good quarter of an hour: «The September Convention must be torn up in the Campidoglio; it is an Italian matter and only the Italians should resolve it. The French will stay on their Seine; an Italian dynasty will go to Rome and only that dynasty can lead us there». Then, with oratorical passion, he exclaimed: «Either Rome comes to Italy or Italy goes to Rome!» Then someone from the crowd shouted: «Death to priests!», but the General immediately quieted the people, and replied: «Death to no one». In truth this anecdote is also reported in the chronicles of visits to other parts of Italy (perhaps it was part of the script). Years later, in 1882, the Military Brotherhood did not fail to record, on stone (see the epigraph on the facade of the building), that Giuseppe Garibaldi, interpreting the vow of the applauding people, exclaimed «Either Rome comes to Italy or Italy goes to Rome».

Forever on horseback

Let’s move on to another of Garibaldi’s stopovers. We proceed along Banchi di Sopra, the entire via dei Montanini and, on the left, via di Sasso di San Bernardino which leads to Giardini della Lizza. Here, once upon a time, stood the Teatro Montemaggi from whose stage Garibaldi gave another speech at the rally organised by the Military Brotherhood and the Workers’ Society. In the book of minutes of the latter, Garibaldi wrote: «I am fortunate to be among you».

But the Gardens of the Lizza have become a place linked to Garibaldi, especially due to the monument that dominates the whole area and on which we can read the simple dedication: «To Garibaldi the Sienese». The task, however, was not easy. In fact, although the decision of the City Council was timely in wishing to honour the Hero in this way (only five days after his death on June 2, 1882), it was not as quick to install the monument that the City intended to place «in the central arch of the portico of Piazza Indipendenza or elsewhere». This was followed by years of discussions between the Municipality, the Volunteer Society, and the Military Brotherhood regarding the best location in which to place the monument. In the end the Lizza was decided upon, although some insinuated that the choice could appear to be dictated more by the need to decorate the public gardens than by the desire to honour Garibaldi.

In 1891, following a competition, the work was entrusted to the sculptor Raffaello Romanelli (who also created the monument to the Fallen of Curtatone and Montanara in the atrium of the University). It was inaugurated on September 20, 1896. The work, besides featuring the proud General on horseback, also recalls, on the sides of the base, some scenes and names of Garibaldi’s victories (Montevideo, Sant’Antonio, Milazzo, Volturno, Varese, Monte Suello, Solferino, Bezzecca, Rome 1849, Aspromonte, Calatafimi, Dijon).

There were also problems at the opening ceremony. It was raining. The authorities were present, the survivors of the Thousand, some representatives of the Masonic Lodges, several Contrada Societies but not the Contradas in official form, since the Archbishop of Siena had asked them not to participate in the initiative. For the occasion, a Palio was also to be run, which, for meteorological reasons, was postponed to the 23rd of the month. It was won by the contrada of the Crested Porcupine, adversary of the Lupa that had been victorious in the Palio of August 1867, witnessed by Garibaldi. It could be said that the General was an equal good luck charm for the two adversaries.

A woman named Italy

From the Giardini della Lizza (the Viale Maccari side), we take Viale XXV Aprile to reach a green area between Via Fruschelli and Via Pannilunghi where, at the end of the 1950s, the monument to the Fallen for Italian Independence was moved, originally located in the centre of Piazza Indipendenza. As already mentioned, it was created by the sculptor Tito Sarrocchi in 1879. The sculpture features a woman, representing Italy, holding the sceptre in her left hand, while with her right hand she places a crown on a wounded and dying lion lying at her feet. On the crown is written «To the brave Sienese fallen for me». Her expression shows both pain and pride.

From the Giardini della Lizza (the Viale Maccari side), we take Viale XXV Aprile to reach a green area between Via Fruschelli and Via Pannilunghi where, at the end of the 1950s, the monument to the Fallen for Italian Independence was moved, originally located in the centre of Piazza Indipendenza. As already mentioned, it was created by the sculptor Tito Sarrocchi in 1879. The sculpture features a woman, representing Italy, holding the sceptre in her left hand, while with her right hand she places a crown on a wounded and dying lion lying at her feet. On the crown is written «To the brave Sienese fallen for me». Her expression shows both pain and pride.

It is said that Sarrocchi’s model had been a Sienese woman. Beautiful and proud, like one of the women that the poet Francesco Dall’Ongaro imagined singing the folk song: «E lo mio amore se n’è ito a Siena, / portommi il brigidin di due colori: / il candido è la fé che c’incatena, / il rosso è l’allegria de’ nostri cuori. / Ci metterò una foglia di verbena / ch’io stessa alimentai di freschi umori. / E gli dirò che il verde, il rosso e il bianco / gli stanno ben con una spada al fianco, / e gli dirò che il bianco, il verde e il rosso / vuoi dir che Italia il giogo suo l’ha scosso, / e gli dirò che il rosso, il bianco e il verde / è un terno che si gioca e non si perde»

Well, one would think that the three-coloured ‘brigidino’ [a type of sweet wafer] made in Siena was very tasty and crunchy, considering the flame with which it was cooked and the recipe that had inspired it. That is to say, metaphors aside, that the Risorgimento of the Sienese was, for those who believed in it, a truly fascinating story.

Produced by: toscanalibri.it

Texts edited by: Luigi Oliveto

Editorial coordination: Elisa Boniello e Laura Modafferi

Photos: Archivio Comune di Siena

Graphic design: Michela Bracciali