6.5 A woman named Catherine

On 18 June 1939 Pope Pius XII declared St Catherine and St Francis of Assisi the patron saints of Italy. On 4 October 1970, the Sienese saint was proclaimed a Doctor of the Church by Pope Paul VI.

But who was this woman?

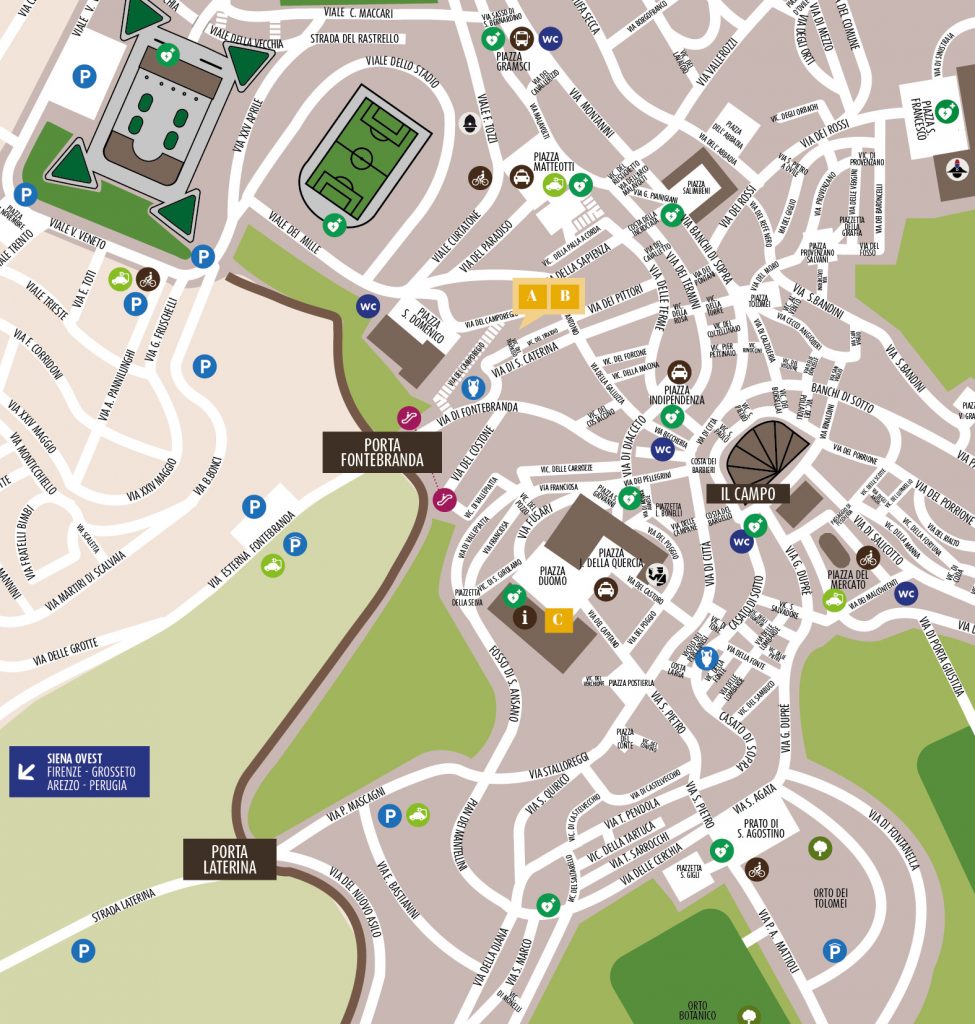

What follows is an introduction to an extraordinary individual from the Middle Ages. This itinerary will serve as a short guide to the most important places connected to the saint’s life and allow you to retrace the key moments of her life.

Catherine was born on 25 March 1347 to Lapa and Giacomo di Benincasa, one of the most prominent merchants and dyers in Siena at the time. She was the family’s 24th child (forgive me for asking myself if her mother wasn’t also deserving of sainthood given the number of children she had). In those days, it was common for women to give birth to a great number of off spring as there was also an equally high infant mortality rate. Lapa herself witnessed the death of many of her children. She, however, lived to the incredible age of 80.

In general, it is very difficult to find out about the lives of women from the past, their stages of growth, their attitudes and behaviour; Saint Catherine, however, is different. A great deal is known about her since her entire, albeit short, life was chronicled by her mother.

Similar to that of Catherine is the story of another well known person from the province of Siena—San Galgano Guidotti, a man who lived on the borderline between sanctity and heresy (also like Catherine) and about whom much is known thanks to his mother Dionisia, who played a key role in the process of canonisation by her accounts of what human reasoning and divine inspiration led her son to make his choices.

Women in the Middle Ages are often portrayed as having suffered lives of submission and moroseness, and it is easy to make the mistake of placing Catherine within this conventional context.

She had her first vision at the age of six when, on her way home from a visit to her beloved sister Bonaventura, Christ appeared before her dressed as a pontiff. Following this extraordinary event, Catherine was convinced that God had chosen her and that Christ had asked her to marry him. From that moment, she devoted herself to Him, never once wavering, except at the age of 12, when her parents convinced her that marriage was a good and proper thing for a young girl of her age, and therefore, in order to arouse the attention of some handsome young merchant’s son, she should take better care of her hair. She tried, but it was a temporary episode and Catherine soon returned to looking after her soul more than her body.

In fact, the relationship that the ‘Girl from Fontebranda’ had with her body was very special. Catherine was born in 1347, one year before the Black Death, an epidemic that devastated Europe. Seeing with her own eyes the consequences of the new waves of epidemics, which were increasingly frequent following that first fatal year, most likely led Catherine to reflect a great deal on physical suffering. She dedicated herself to caring for the sick, including victims of the plague, throughout her life; for this work, she was also declared patron saint of the Corpo delle Infermiere volontarie della Croce Rossa Italiana (Corps of Voluntary Nurses of the Italian Red Cross).

Her life was thus characterised by self-denial and love of neighbour. It is imperative, however, not to imagine Catherine as a person who spent her time secluded from the larger world, absorbed in prayer and helping those in need. On the contrary. she had an impressive public life, writing thundering letters to rulers all over Europe—even to the pope—reminding them to follow the teachings of the Gospel.

Catherine played a prominent role as ambassador for the Republic of Florence, with the aim of convincing the pope to return to Rome with his court. The papal court had been established in Avignon in 1309; the reasons for this choice were due to various factors, such as the state of decay into which the Eternal City had fallen and, above all, the fact that the majority of the cardinals in the Curia were of French origin.

It was not until 1377, a year marked by the forcible intervention of the Sienese saint, that a proposal to return the pope to Rome was discussed. While France was more than pleased to host the papacy, the absence of the ‘Vicar of Christ’ in Rome was becoming burdensome, as was already evident in the malaise and disorientation affecting Christianity throughout the Italian peninsula.

It would be incorrect, though, to attribute Florence’s appeal to the pope via Catherine to a mere question of faith, free of any political motives; in fact, the reasons why the papal court was expected to return to Rome were clear.

Since the pope had left, the Eternal City had been administered by papal vicars who were not held in any esteem and were, therefore, unable to deal with the constant city riots stirred up by the opposing political parties. To add insult to injury, Florence was also attempting to increase the discontent of the Roman citizens with these papal substitutes.

So it was that Catherine departed for Avignon, no stranger to Pope Gregory XI, who had already received fiery and admonitory letters from her regarding his activities. The pontiff had been aware of her for quite some time and, in a bid to keep her under control, had assigned her a confessor, a ‘righteous’ man, whose duty was to determine whether or not this extravagant woman who fasted, who assisted the sick, and who scourged herself to punish her body was worthy of the fame that preceded her.

As was previously mentioned, so much is known about Catherine through the testimony of her mother, but who was it that questioned Lapa? In fact, it was the confessor sent by the pope, Beato Raimondo da Capua (Blessed Raymond of Capua), who immediately understood the depth possessed by the woman he found before him. The key point to take away from all this is that it was a woman—not a man—who employed her authority and zeal to obtain the return of the Holy See to Rome.

The Shrine of the House of St Catherine

Obviously, it is necessary to begin with the place where Catherine was born: her house, now a shrine dedicated to her. It is located in the Nobile Contrada dell’Oca, which is why Catherine is also called the ‘Santa dell’Oca’, even though the contrada as we know it today did not yet exist. Entering the courtyard in front of the house- shrine, we find ourselves in a space known as the Portico dei Comuni d’Italia, so named for the Italian ‘comuni’ (municipalities) that each contributed the cost of one brick to the city of Siena for the portico’s construction, a symbolic gesture to highlight that Catherine is the saint of all Italy. The entrance door to the house-shrine is an admirable work of wrought iron representing the exchange between the Sacred Heart of Jesus and that of Catherine.

L’Orartorio del Crocifisso

(The Oratory of the Crucifix)

On the right is the Oratorio del Crocifisso, a 17th century church that represents one of the best examples of Baroque art in Siena. Its name derives from the painted crucifix that hangs inside and before which, according to tradition, Catherine received the stigmata. The cross is one of the oldest in existence in Tuscany, dating back to the 12th century. Together with St Francis, Catherine also received the wounds of Christ on her body, but unlike those of the saint of Assisi—or the more recent San Pio da Pietralcina (also known as Padre Pio)—which were tangible, Catherine’s were not made visible, in accordance with her desire to participate in the experience of the suffering endured by Christ on Golgotha privately and without pity.

L’Oratorio della Cucina

(The Oratory of the Kitchen)

On the left is the Oratorio della Cucina, the oldest part of the Benincasa family home and the room which served as the kitchen. Today this room is entirely decorated with late 16th century paintings depicting episodes from the public life of St Catherine. The works housed within are an excellent and detailed guide to the key moments of her life.

On the right hand wall are:

–Il Papa Torna a Roma by Alessandro Casolani (1583).

The fundamental role of St Catherine in bringing the Pope back to Italy has already been discussed; without her, the Vatican would most likely not be the seat of the pontiff today.

–Lo Sposalizio Mistico di Santa Caterina (The Mystical Wedding of St Catherine) by Alessandro Casolani and Bartolomeo Neroni, known as Il Riccio (1570). Also previously mentioned was the fact that St Catherine became the bride of Christ, the portrayal of which follows a rather traditional iconography and occurs with the intercession of the Virgin Mother of God.

-On the altar, painted on a panel, is the depiction of Santa Caterina che Riceve le Stimmate (St.

Catherine Receiving the Stigmata) by Bernardino Fungai (1495).

-On the wall immediately to the left is the painting of Santa Caterina Libera un’Ossessa (St Catherine Exorcising a Possessed Woman) by Pietro Sorri (1587). One of the various tasks of the Dominican order included confession, a practice that Catherine, as a tertiary of the order, used to perform, especially for those condemned to death.

One of the various tasks of the Dominican order included confession, a practice that Catherine, as a tertiary of the order, used to perform, especially for those condemned to death.

-On the opposite wall is the Canonizzazione di Santa Caterina (Canonisation of St Catherine) by Francesco Vanni (1600).

It was the Sienese Pope Pius II, born Enea Silvio Piccolomini, who proclaimed her a saint in 1461.

In addition to the paintings, the floor, made of original 16th century tiles, is also a wonderful work of art to be admired.

L’Oratorio della Camera (The Oratory of the Bedroom)

Past the bookshop is a slippery travertine staircase leading down to the basement, where the ‘Catherine’s bedroom’ is located. It is frescoed with scenes from Catherine’s childhood by Alessandro Franchi, a well-known representative of the Scuola purista of 19th century Siena who was involved in important projects in the city, such as the creation of the golden mosaics on the façade of the Duomo and the restoration of part of Beccafumi’s inlay work under the dome inside the cathedral.

Here, in a style decidedly different from that found on the upper floor, the stories of Catherine’s life are once again told, starting from her childhood with the Taglio dei Capelli (The Haircut), La Madre che Vede la Figlia Salire le Scale Sospesa (The Mother Sees Her Daughter Levitating up the Stairs), and Il Padre della Santa la Vede con una Colomba Bianchissima in Testa (The Saint’s Father Sees Her with a Brilliant White Dove on Her Head); continuing with the Dono di un Abito a Gesù in Veste di Pellegrino (The Gift of a Robe to Jesus in Pilgrim’s Clothing), another Le Nozze Mistiche (Mystical Wedding), the Madonna Che Dona suo Figlio Gesù alla Santa (The Madonna Giving Her Son Jesus to the Saint), and lastly, Gesù Cristo Offre alla Santa Due Corone, Una di Spine e Una di Gemme (Jesus Christ Offering the Saint Two Crowns, One of Thorns and One of Gems).

La Basilica di san Domenico

La Cappella della Volte

Leaving the sanctuary, take the road on the left going uphill (everything is always uphill in Siena) towards the Basilica Cateriniana of San Domenico, another fundamental stop on the route as it is was the saint’s preferred place of worship. For her, contemplation was always alternated with activity. Although she led an existence similar to that of a monk, Catherine was a ‘tertiary’, meaning that she was never cloistered but had the freedom to move among the people, a ‘public’ life that was truly out of the ordinary.

Immediately to the right upon entering the basilica is the Cappella delle Volte (Chapel of the Vaults), a place where she used to remain for hours in prayer and where, according to tradition, a number of prodigious events took place. Here among the 17th century paintings depicting episodes from her life can be found what is considered to be Catherine’s ‘portrait’, a fresco by Andrea Vanni, an artist who knew the saint personally, a fact which gives the idea that the figure in the painting, although certainly idealised, is what Catherine actually looked like.

La Cappella della Sacra Testa

(The Chapel of the Holy Head)

On the right side of the nave of the basilica, some of the personal belongings of the ‘Girl from Fontebranda’ are displayed in a glass case, including the cilice she used for corporal punishment.

Another important relic is kept inside the adjacent chapel built on the occasion of her canonisation by Pope Pius II in 1461, which also promoted her cult. The pontiff realised the importance of propagating the cult of such a powerful and righteous figure in a century as troubled as the 15th century was proving to be.

As one approaches the balustrade made of yellow marble from the Montagnola Senese, the important relic becomes visible: the venerated head of the saint.

Apart from other small relics scattered around the country, the rest of St Catherine’s body is buried in the Basilica of Santa Maria sopra Minerva in Rome.

The Oratory of St Catherine of the Night

Traces of St Catherine, statues and epigraphs, exist throughout the city. For us, though, after having learnt about both her childhood and adult life, the last stop on our journey is the place where Catherine nursed the ill: the historic Ospedale di Santa Maria della Scala. In this grandiose complex—described in the previous brochure—the direct link to the work of the Sienese saint is located underground, in the Oratory of Santa Caterina della Notte, the room where she used to fall asleep exhausted following long hours of nursing the sick and needy.

Here, amidst the skulls and 17th–18th century decorations that serve to remind us of the transience of life, it is possible to see the place where, according to legend, Catherine slept, which is occupied today by an 18th century statue.

Text by Ambra Sargentoni (Ambra Tour Guide) Editorial coordination: Elisa Boniello and

Laura Modafferi

Photos: Archivio Comune di Siena, Leonardo Castelli, Graphics: Michela Bracciali