6.9 Pride, women, and the Republic

La Lizza

This tour will lead you back to the glorious Republic of Siena in the 15th century, a Siena that fought against the oppression of the Spanish imperial power.

The activities of Pandolfo Petrucci, especially his manoeuvring between the fluctuating political powers of the time, ensured that Siena was not subjugated between the end of the 15th and the beginning of the 16th centuries; unfortunately, the military and diplomatic dimension of the superpowers in the 16th century was certainly not comparable to that in which the Republic of Siena had found itself operating up to that time, committed as it was to resisting the pressures of Florence. To avoid being conquered by Florence—a fate that had already befallen Pistoia, Pisa, and Arezzo—the Republic requested military aid, first from Emperor Charles V and then, as we shall see, from Henry II of France.

Let’s take a closer look at the dynamics of the European powers which indirectly influenced the development of Siena’s political situation: on one side, there was Francis I, the king of France and father of the aforementioned Henry II; on the other, Charles V, Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. The latter inherited a vast territory to rule: from his mother, Joanna the Mad, he received the territories of Spain, the Castilian West Indies, and the Aragonese kingdoms of Sardinia, Naples, and Sicily, while from his father, Philip the Fair, he received the title of emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, which included Flanders and the German territories.

Since France had also claimed possession of southern Italy, tensions were ongoing and led to several direct clashes, the most famous of which was the Battle of Pavia in 1525. On that occasion, Charles V, who could avail himself of an alliance with England and the papacy, possessed a sizeable numerical advantage over the French monarch, a factor that led to victory. Francis I was captured by the imperial forces and his ransom, as stipulated in the Treaty of Madrid of 1526, forced him to renounce his claims to the territories of southern Italy and give up control of those he had already conquered, such as the Duchy of Milan. On his return home, Francis declared the treaty he had signed with the Emperor null and void and entered into an alliance with the Republic of Venice, the Papal States, the Duchy of Milan, the Republic of Genoa, and the Florentine Republic—those territories that had felt threatened by the growing hegemony of imperial power—which was known as the League of Cognac.

The emperor did not like this sudden change of alliance on the part of the Italian states and, in 1527, he put the city of Rome to fire and sword, historically known as the Sack of Rome, with an army largely made up of mercenary Lansquenets of the Lutheran faith who had been left without pay, among other things, and were given virtually free reign to sack the papal city.

Faced with this perilous situation, Pope Clement VII fled to Orvieto. Feeling directly responsible for what had happened in Rome and mortified by the many innocent people who had lost their lives as a result of his choices, he stopped shaving his beard as an act of condolence. Due to this particular fact, it is possible to deduce, when looking at portraits of the pontiff, which phase of the pontificate they date from, precisely on the basis of whether or not he has a beard. Clement VII was a member of the Medici family, the nephew of Lorenzo the Magnificent, who resided on the Chair of Peter from 1523 until 1534, the year of his death. Desirous of regaining control of Rome and returning Florence to the hands of his family members, the pontiff entered into negotiations with Charles V who, for his part, had an interest in receiving the crown of the Holy Roman Empire—as well as taking advantage of papal support to drive off the Ottoman advance. The new alliance was also sealed by a marriage, that of Margaret of Austria, Charles V’s daughter, and Alessandro ‘the Moor’, the pope’s illegitimate son. After a long siege of Florence by the imperial troops, the Medici managed to return to the City of the Lily, regaining the government and establishing, for the first time, a real duchy. Such contextualisation is fundamental to understand the way in which the Republic of Siena moved within the framework of alliances. During the phase in which Francis I and Clement VII were allied in the League of Cognac, Siena appealed to Charles V in an anti Medici capacity. In support of the city, the emperor sent a number of his troops, led by the commander Diego Hurtado de Mendoza. Initially, the alliance with the Spaniards seemed to yield positive results, as was evidenced by the support of Spanish troops in the Battle of Camollia in 1526, a battle that led to the defeat of the Florentine papal army.

As mentioned above, however, the rivalry between the pope and the emperor was a multi faceted and ever evolving affair; thus, at the moment when Clement VII and Charles V established their new alliance, Siena’s political and diplomatic position shifted radically. The city had also witnessed this change of course from within. At first, Diego de Mendoza had presented himself as the ‘defender’ of the city, but shortly after his arrival in Siena, he imposed a decisive increase in taxes—with the pretence of needing to invest in the strengthening of the city’s defences—and called for the disarmament of the city; such demands highlighted the ambiguity of the Spanish protection project and fuelled suspicions about the good faith of Charles V’s contingent.

There was more. Mendoza also asked for the ‘scapitozzamento’ (a specific term that means ‘razing’) of the medieval towers in order to repurpose the stones and bricks for the construction of a new fortress. This new defensive structure was built here at La Lizza, but it did not resemble that which stands today; instead, it was an L shaped fortress built to defend the Spanish regents, who had taken refuge within, from the citizens of Siena.

Il vicolo dello Sportello

By then, it was clear that the Spanish faction was not preparing for a battle with the enemy Florence, but rather for military occupation. These reasons led the Sienese, in 1552, to stage a revolt and storm the fortress.

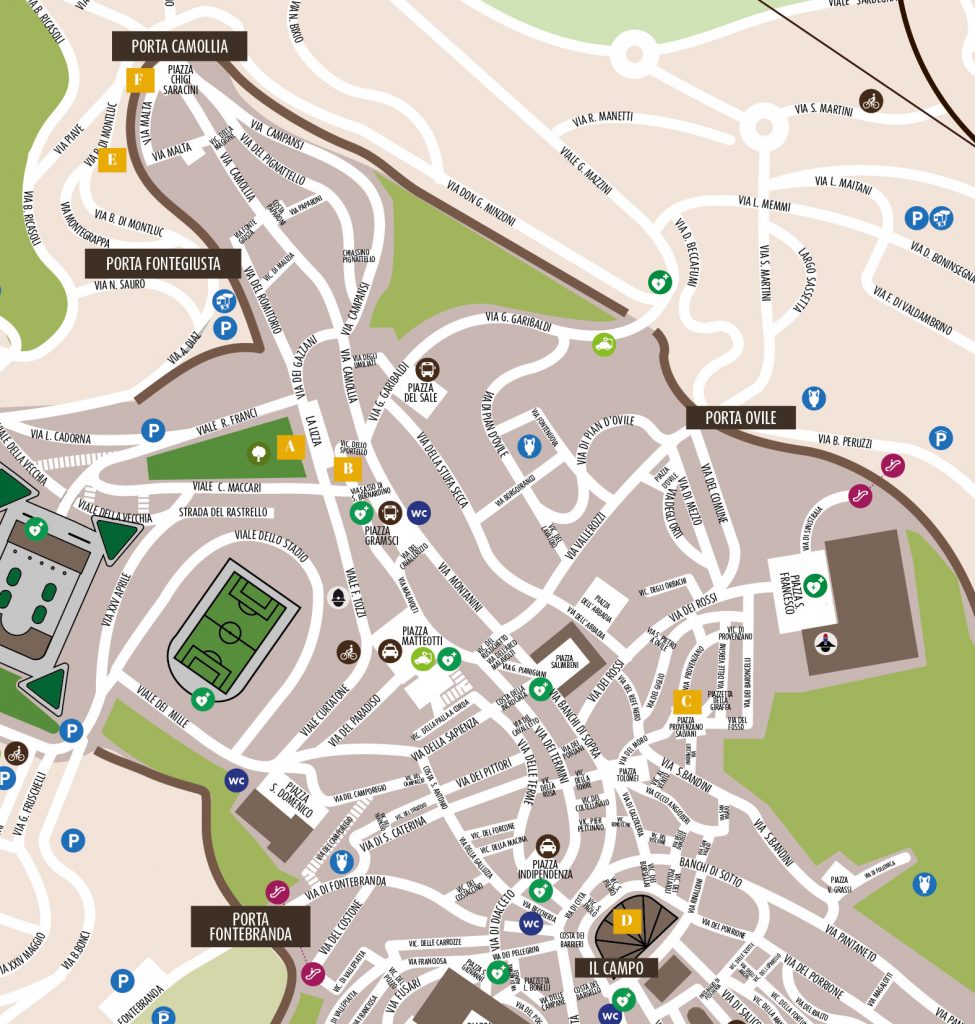

Let’s put the central statue of Garibaldi behind us and cross the street, going towards vicolo dello Sportello (Alley of the Door).

A massive wall connected the defensive structure to the old walls circling the city. The street with the emblematic name corresponds to the point where a small door had been built in the wall which served as a secondary access to the fortress in question.

It was through this small door that the Sienese passed to successfully conquer the fortress and seize control.

Although the will of the people was to brutally drive out the imperial gendarmes, Siena had not yet abandoned hope of Charles V’s possible assistance in case of future need against the Florentine threat. Thus, the garrisons were allowed to depart the city with the dignity of their arms.

Piazza Provenzano

Next, walk along Via di Montanini until you reach Piazza Tolomei. Turn left behind the church and continue on until you arrive at Piazza Provenzano Salvani.

This is the place where, during the historical period of the Spanish alliance, an event took place that was destined to leave its mark on Sienese religious devotion.

It is said that one evening during the last stages of the occupation, a Spanish gendarme, most likely drunk, took up his weapon and, for reasons that have never been fully clarified, shot at a small statue of the Madonna set in a niche in this square. It fell to the ground and shattered; miraculously, though, the effigy was not completely destroyed; the bust remained intact from shoulder to head.

The miracle of the Madonna di Provenzano, as the event is known, is the origin of the cult of the simulacrum, which is also linked to the Palio on 2 July.

The bust of the Madonna rests on the altar of the church, and since that distant evening in the 1500s, has never once stopped working miracles for her faithful.

Piazza del Campo

Leaving Piazza Provenzano Salvani, we return once again to Via Banchi di Sopra, passing through Piazza Tolomei to arrive in Piazza del Campo.

Once the empire and the papacy had reconciled after the Sack of Rome, France formed an alliance with Siena in the 1550s, which was considered an excellent vantage point for keeping the papal state and Florence under control.

Not all the Sienese population was happy about the new alliance. The two representatives sent by France, Ippolito d’Este (cardinal of Ferrara) and Piero Strozzi (a Florentine exile), were not sufficiently aligned, and this only increased the anti French feeling among the citizens.

These were very difficult and delicate years, when Siena was besieged by the imperial troops led by Gian Giacomo de’ Medici, Marquis of Marignano. Soon finding himself excluded from the game, Cardinal Ippolito was replaced by the commander Blaise de Montluc.

Born around 1500 in a small village in Gascony, not far from Condom, Blaise exhibited from a very young age a particular inclination for arms and battlefields, which led him to soon leave his native village for the Lorraine court, where he had the opportunity to attend cavalry school and where he was appointed court page.

A born fighter, he distinguished himself in several battles between France, Spain, and Italy, despite suffering from malaria and chronic dysentery since childhood. When Henry II, heir of Francis I, entrusted Blaise with the task of commander in the war of Siena, it was during a time when Blaise was also beset by severe toothaches. Despite being advised against leaving by his doctor, his passion for Italy and the stories he had heard about Siena, combined with his sense of duty, drove him to set sail for the peninsula. When it was about to be decided who would replace Cardinal d’Este, the royal council had initially rejected Montluc because of his bad temper. According to the council, he was too choleric and moody, and would certainly never get on with the disposition of the Sienese. Indeed. He was sure to compromise the interests of France. In the end, however, he was chosen.

After all, the reasoning went, there is no authority, no one who can assume great responsibility, who can put order and justice in place, who is a person of action and a great achiever when it comes to leading people into battle, without also being choleric, moody, and bad tempered.

And so Blaise’s great adventure in Siena began. The time he spent at the head of the Franco-Sienese contingent, from 1553 to 1555, was characterised by the most extreme suffering of the latter. Coupled with the level of exasperation that the troops had reached, forced to defend themselves on several lines, kept open while the pro imperial contingent narrowed the Sienese front with a ‘pincer’ strategy, some of the darkest and most dramatic episodes in the city’s history took place, including the ‘strage delle bocche inutili’ (massacre of the useless mouths). When food supplies were no longer sufficient for the entire population of Siena, it was decided to drive the women, the elderly, and the children— known as the ‘useless mouths’ because they could not fight—out of the city, accompanied by a sizeable armed contingent.

The enemy army besieging the city walls had no mercy for them either. It killed the escort and the elderly; the women, after being raped, and even the children suffered the same fate as the others.

These horrors were recorded by Blaise in a kind of diary—the Commentaries—but he also noted down the extraordinary moments he experienced, such as those related to the incredible courage of the women of Siena.

Il fortino delle donne

From Piazza del Campo, follow Via di Banchi di Sopra and then Via di Montanini until you reach Porta Camollia. Immediately outside the entrance arch, on the left, is what remains of the Fortino delle Donne (Women’s Fort).

This is a military fortification which was most likely designed by Baldassarre Peruzzi. Conceived to house both cannons and harquebuses, with a firing angle of about 180 degrees, the fort was an enormous firearm ready to defend the city on its weakest side, the north.

It was most likely Blaise himself who named the fort after the women of Siena, because he was genuinely impressed by the way in which they rolled up their sleeves to help the men with everything, even destroying their own houses to obtain bricks to reinforce the city walls.

Thanks to the strength and valuable cooperation of three Sienese noblewomen who captained the army of women—Laudomia Forteguerri, Fausta Piccolomini, and Livia Fausti—they played a featuring role in the French commander’s memoirs. He wrote, ‘It will never be, O Sienese women, that your name will not be immortal as long as the book of Montluc lives, for you are truly worthy of immortal praise, if ever women were’. Then, ‘They had composed a song in honour of France which they sang on their way to their fort; I would give my best horse to have it and to transcribe it here’.

At the end of this strenuous and valiant resistance, Siena was forced to surrender. In 1555, the Florentines, allied with the imperial army, prevailed. The conquest of the city, however, was not by the Medici, but by the emperor. Florence cunningly asked the emperor for a large sum of money as compensation for its military aid during the war. Following the Peace of Cateau Cambresis in 1559 between France and Spain, in which an agreement was signed defining the division of the conquered Italian territories, Florence was given the Republic of Siena as a reward, which thus became the new duchy owned by the City of the Lily.

The Arch of Porta Camollia

To Commander Blaise, who led Siena to a noble and combative end, is dedicated this busy street that runs along the walls to the north of the city. Above the central arch on the outer side of the gate, the scene of Siena’s valiant last stand, one can read the inscription «Cor magis tibi Sena pandit», or «Siena opens its heart to you, wider than this gate».

Obviously, this motto is hypocritical, engraved as it was in 1601 by the Grand Duke of Tuscany, Ferdinando I, son of Cosimo I, who had boasted a few years earlier of having conquered the city on his own merit, in a bold attempt to garner respect from the people of Siena.

Text by Ambra Sargentoni (Ambra Tour Guide) Editorial coordination: Elisa Boniello and

Laura Modafferi

Photos: Archivio Comune di Siena, Leonardo Castelli, Sabrina Lauriston

Graphics: Michela Bracciali