1.9 Siena, the city devoted to Mary

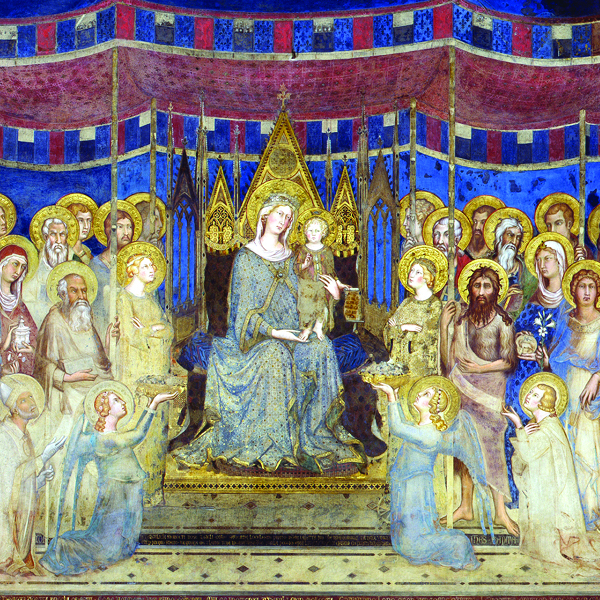

There is an indissoluble bond that connects Siena to Mary, Mother of God who, over the centuries, has become the very identity of the people of the city. It is to her that the Sienese turn as Queen and Advocate, as Mother of Grace for the city. A relationship that transcends the afterworld and finds its sublimation in the most representative places of the city itself. In Piazza del Duomo, the Cathedral is dedicated to the Assumption, the Palazzo Comunale, and houses the marvelous Majesty of Simone Martini, in which she dominates surrounded by Saints, showing the governors the Savior of the World and warning them about the conduct to be adopted to ensure well being and prosperity in Siena. La Torre del Mangia, in the interpretations of most, can be seen as a white lily, traditional emblem of the purity of the Virgin.

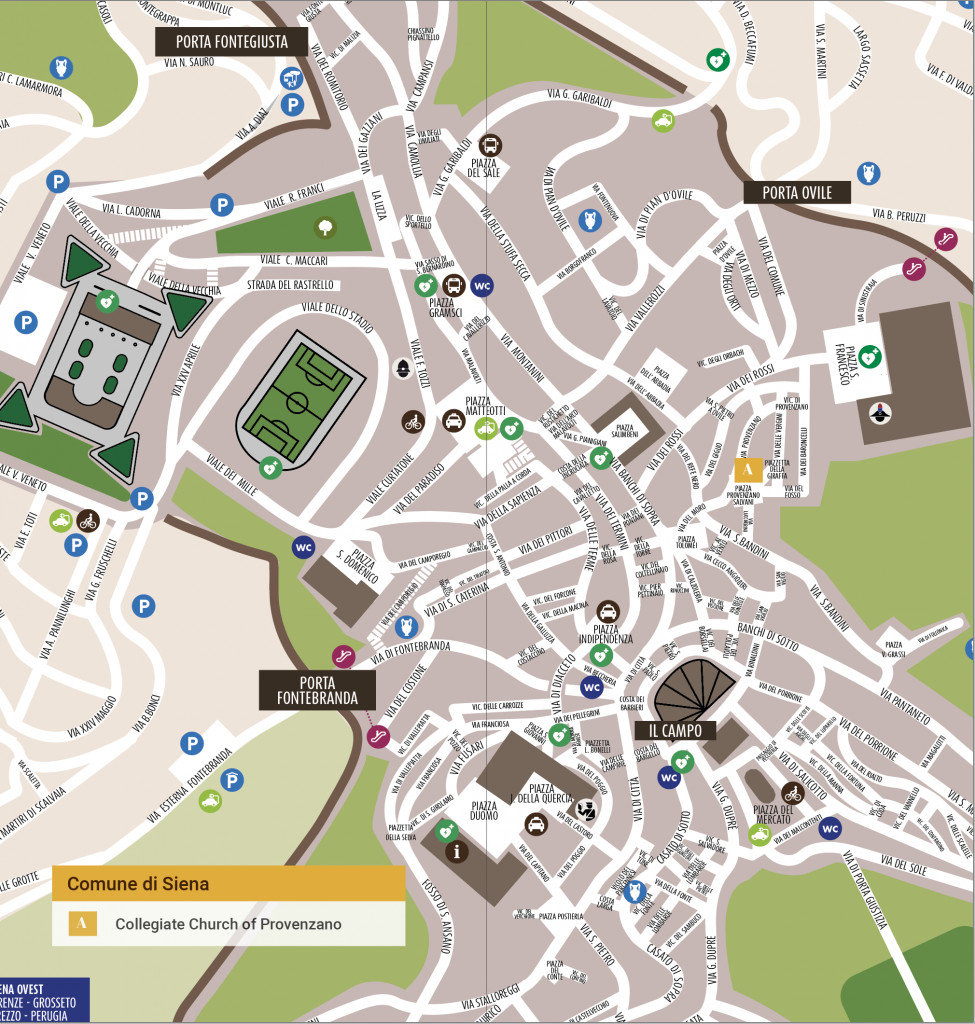

The ‘Campo’ (field), the square in front of the Palazzo Pubblico, could refer to Mary’s mantle, with which she covers and protects those who entrust themselves to her, as depicted in many paintings. The facade of the Public Palace has traces of twelve gates, such as the Jerusalem of the Apocalypse, the city of God, of which Our Lady is a model. Right below the tower where one can see the Chapel, a votive offering following the Black Plague, transforms the square into an immense openair church. The indissoluble bond between Siena and the Virgin had its final consecration in 1260, the year of the battle of Montaperti, in which the Sienese defeated the Florentine troops. On the eve of the battle, the citizens, led by the magistrate Buonaguida Lucari, gathered in the Duomo to pray to the Virgin, offering her the keys of the city and pleading for her protection. The day after the victory of Montaperti, the Florentine painter Coppo di Marcovaldo, made prisoner by the Sienese after the battle, was forced to save himself by painting for Siena a painting of the Madonna on the throne, currently kept in the Basilica dei Servi. In the meantime, the city statutes praised Mary as Lady of Siena and coins were minted carrying the inscription “Sena vetus civitas Virginis” (Ancient Siena, city of the Virgin); the seals of the Republic affixed to each document presented the image of the Madonna and Child, accompanied by the words “Keep the Virgin the ancient Siena which she makes beautiful”: devotion to Mary became a sign of cultural identity.

Collegiate Church of Provenzano

Over the centuries, the veneration of the Sienese for the Blessed Mother has never ceased. Towards the end of the sixteenth century, during a period of plague and famine, the city authorities went to one of the most infamous neighborhoods of Siena, in front of a miraculous terracotta image of the Madonna and made her a vow to build a large church, the Collegiate Church of Santa Maria in Provenzano. On summer days, when the whiteness of the Collegiate Church solemnly shines the light and the details of the church, Piazza Provenzano seems to flood with a metaphysical solitude. Only the days of the Palio will bring it back to a practical measure, populating it with colors and sweaty humanity. And of passionate devotion, because the church of Provenzano, dedicated to the Visitation of the Virgin, is, together with the Duomo, the other pole of Marian worship, notoriously rooted in Siena for its atavistic heritage, so much so that it has referred to the city as “Civitas Virginis”. From this comes also the reason of the two palii dedicated to the Madonna: the Assumption, invoked in the gothic impulses of the Cathedral; the one, in the semblance of fragile terracotta, worshiped in the Collegiate Church of Provenzano. The history of the Collegiate Church of Provenzano is the umpteenth testimony of how in Siena of the sharp contrasts (black and white is the emblem) also the virtue finds always its opposite equal. Let’s narrate it this way. Towards the end of the sixteenth century, from the numerous convents present in the city came the virginal songs of “Salve regina”, but equally audible and equally touching was the countermelody of the prostitutes whose registry office showed, at the time, really important numbers. Just after the neighborhood of Provenzano (from the name Provenzano Salvani, who had had his prestigious home here) could offer a wide choice of brothels and qualified professionals. Among the most famous was, for example, Vi- ola, which even earned the title of a street still existing with this name. The Viola street is part of a maze of narrow streets with unique names: via delle Vergini, via del Giglio, once there was also via del Buco (later became via Baroncelli). Toponymy, in short, dictated by the sarcasm of the people and which went to mark the map of a neighborhood. The already flourishing trades reached economic miracle figures towards the middle of the sixteenth century, at the time of the Spanish domination, thanks to the soldiers of don Diego Hurtado of Mendoza, who were gathered in the convent of San Francesco, and could easily reach the very close streets of the señoritas. No one, however, would have ever imagined that the (red) lights of those slums could one day fade behind the sparkle of an imposing temple, the Collegiate Church of Santa Maria di Provenzano.

Between history and legend this happened. Near the area where the Collegiate Church stands today, on the facade of one of those very badly reputed houses there was a chapel representing a small Pietà. A Spanish soldier in the mood of bravado had the idea of firing an arquebus against the tabernacle. The shot shattered most of the bas relief, but the weapon imploded in the hands of the soldier who died instantly. It was July 2, 1594 and already a year later the construction of the church was begun, completed in 1604, which would preserve the bust of the Virgin remained untouched by the sacrilege and already prodigal of miracles. At that point the prostitutes, except for a few who had converted to another life, had to quarter themselves elsewhere. A vibrant synthesis of the events related to the ‘restoration’ of the district is written in Latin on a wall in Via Provenzano Salvani. In the plaque placed there in 1723 by the knight Alcibiade Lucarini Bellanti, vicar of the church of Provenzano, we read: “Stop a moment on the road, as long as the image of the Blessed Virgin Mary does not pass unnoticed here. All this area of Provenzano was exposed to the prostitutes, but after the virginal star shone like a mist that plague dissipated, the brothel from here disappeared and, coming from all over the Sienese devotion, was erected the nearby church where the sacred image is venerated by a large influx of people. The temple immediately became the center of devotion. They asked the “Madonnina” for prodigiously paid graces. And it was worshiped not only by the people but also by nobles. On all the Medici governors, who had substantially financed the building of the church. Caterina de’ Medici, governor of Siena from 1627 to 1629, ordered, before she died, that her heart be buried in Provenzano as a pledge to the devotion she nurtured for that Madonna. And also the viscera of Prince Mattias, who died on October 11, 1667, found burial in the Sienese Collegiate Church.

We know, then, in what way the veneration for the Madonna of Provenzano has mixed with the history of the Palio. It was in the first decades of 1600. As amusing as the horse races along the city streets could be, with which the celebrations for the Assumption ended in midAugust, they lacked, however, the spectacularity that the closed scenery of Piazza del Campo could have offered. For this reason, they also began to organize the palio “alla tonda” on the outer ring of the Camp. Moreover, it was at this time that the Contrade acquired an increasingly decisive role in these rides. In 1656 the palio “alla tonda” will thus have its own codification and regular frequency, as well as an explicit dedication to the Madonna: from now on, every 2nd July, a palio will be held in honor of the Madonna of Provenzano, on the day, that is, on which that image had suffered the offence. It is therefore following the tradition of this story that, still today, when the palio is won, the Sienese break into the baroque penumbra of Provenzano to sing their Maria mater gratiae. An ancient prayer, suggested in liturgical books since 1300 and that, marked by the ways of Gregorian chant, in Siena has become an incredibly popular chant. Walking along the streets of Siena, it is possible to come across numerous road tabernacles consecrated to the Madonna. On September 8th of every year, a feast dedicated to the Madonna, the children of the seventeen Contrade compete to embellish the tabernacle in their district with the most beautiful drawings and garlands. This is a very heartfelt tradition in Siena, which contributes to keep alive the love for the Protectress of the city.

Brochure edited by Toscanalibri.it

Texts edited by Cristiano Pellegrini Editorial coordination:

Elisa Boniello e Laura Modafferi

Photos: Primamedia, Sabrina Lauriston e Leonardo Castelli

Graphic design: Michela Bracciali