2.4 A Romantic Walk

The promenade of the Lizza

The name itself says so. It is called the Lizza because, at the end of the sixteenth century, it was the space for tournaments and equestrian exercises. Until, in 1779, plans were made to develop the area by transforming it into a public walkway and Antonio Matteucci was commissioned to design it as a garden. And thus it remained, a garden which anticipates the larger and airy spaces of the Medici Fortress. Until the middle of the twentieth century, it was really the place to walk, meet, with a worldliness within everyone’s reach. When there were no buildings built in the modern era, the view could sweep over the panorama of the city, where, against the sky, the spires of the duomo, the Torre del Mangia, the basilica of San Domenico, the roofs of the houses are carved out. In short, a luxury garden but within reach of everyone, very appreciated even by outsiders. Along its avenues walked distinguished guests such as Arthur Symons, Vernon Lee, Henry James, Paul Bourget, Giovanni Marradi, Giovanni Comisso, Carlo Betocchi, Leonardo Sciascia.

Where the Palazzo di Giustizia stands today (the work of the architect Pierluigi Spadolini, built at the end of the Seventies of the last century), the teatro Montemaggi stood (named after its designer Francesco Montemaggi), inaugurated in 1861. There were lyrical works, exhibitions and cultural initiatives. On February 19, 1933, following heavy snowfall, the roof collapsed and the entire structure was damaged. After the war, a dancing hall was set up among the remains of the theatre (the Garden of lime trees). On Sunday, instead, the city band performed on a stage set up in the gardens, while the traveling photographer portrayed soldiers and very engaged couples, proud to pose love which you could only say was eternal at the time. On this small, tenderly Provincial world stood the monument to Giuseppe Garibaldi, inaugurated in 1867. From the top of his steed, the hero of the two worlds reiterated the myth of himself and the rhetoric of a homeland story. For the Sienese, the Garibaldi Della Lizza has always been someone to confide in, to the point that a starlet sung in the districts of Siena can tell him without problems: «And Garibaldi in Siena complains, / because he does not want to be in the Lizza, / girls go there to make love / and the ruffian does not want to go past».

Where the Palazzo di Giustizia stands today (the work of the architect Pierluigi Spadolini, built at the end of the Seventies of the last century), the teatro Montemaggi stood (named after its designer Francesco Montemaggi), inaugurated in 1861. There were lyrical works, exhibitions and cultural initiatives. On February 19, 1933, following heavy snowfall, the roof collapsed and the entire structure was damaged. After the war, a dancing hall was set up among the remains of the theatre (the Garden of lime trees). On Sunday, instead, the city band performed on a stage set up in the gardens, while the traveling photographer portrayed soldiers and very engaged couples, proud to pose love which you could only say was eternal at the time. On this small, tenderly Provincial world stood the monument to Giuseppe Garibaldi, inaugurated in 1867. From the top of his steed, the hero of the two worlds reiterated the myth of himself and the rhetoric of a homeland story. For the Sienese, the Garibaldi Della Lizza has always been someone to confide in, to the point that a starlet sung in the districts of Siena can tell him without problems: «And Garibaldi in Siena complains, / because he does not want to be in the Lizza, / girls go there to make love / and the ruffian does not want to go past».

Grand Hotel

The opening of the Grand Hotel de Sienne in 1875 (which later became the Grand Hotel Royal) helped increase the prestige of the Lizza significantly, in the sixteenth-century palace that belonged to the Zuccantini Zondadari (the building on the left at the corner with via del Sasso di San Bernardino and with an entrance in via dei Montanini 101). The municipality of Siena had even issued a notice to facilitate the opening of a modern hotel with financial incentives.  The work was done by a Florentine entrepreneur, Filippo Betti, who managed to create a structure in tune with the times. On tourist guides, almanacs, newspapers, the hotel was immediately advertised for its “modern comfort” and for the “enchanting view” over the Promenade of the Liza. The two dining rooms featured hanging crystal chandeliers, the cutlery was silver, people could spend relaxing moments in the reading room or in the garden equipped with armchairs and tables. Early twentieth century advertising campaigns provide details on how it is equipped with electric light, central heating, elevator (it was one of the first elevators installed in Siena), rooms with bathrooms, running hot and cold water. And «special arrangements for long stays in summer, autumn and winter» were also possible. All this considered, the Grand Hotel Royal hosted, over almost sixty years, nobles, rulers, particularly demanding outsiders. Among them, in 1892, Henry James, who, in his book of travel Italian Hours, on the pages dedicated to Siena, waxes forth on the atmosphere of the Grand Hotel, «the still fresher flower of modernity, takes on to my present remembrance a mellowness as of all sorts of comfort, cleanliness and kindness». Not without the mixture of lights which go out so as not to light up again, the Grand Hotel closed for good in July 1932. The bronze sphinxes decorating the staircase were seen by beautiful people. On this occasion they too, contrary to their proverbial imperturbability, let out a sense of sadness.

The work was done by a Florentine entrepreneur, Filippo Betti, who managed to create a structure in tune with the times. On tourist guides, almanacs, newspapers, the hotel was immediately advertised for its “modern comfort” and for the “enchanting view” over the Promenade of the Liza. The two dining rooms featured hanging crystal chandeliers, the cutlery was silver, people could spend relaxing moments in the reading room or in the garden equipped with armchairs and tables. Early twentieth century advertising campaigns provide details on how it is equipped with electric light, central heating, elevator (it was one of the first elevators installed in Siena), rooms with bathrooms, running hot and cold water. And «special arrangements for long stays in summer, autumn and winter» were also possible. All this considered, the Grand Hotel Royal hosted, over almost sixty years, nobles, rulers, particularly demanding outsiders. Among them, in 1892, Henry James, who, in his book of travel Italian Hours, on the pages dedicated to Siena, waxes forth on the atmosphere of the Grand Hotel, «the still fresher flower of modernity, takes on to my present remembrance a mellowness as of all sorts of comfort, cleanliness and kindness». Not without the mixture of lights which go out so as not to light up again, the Grand Hotel closed for good in July 1932. The bronze sphinxes decorating the staircase were seen by beautiful people. On this occasion they too, contrary to their proverbial imperturbability, let out a sense of sadness.

Luxury homes

The nearby palazzo Bernardi Avanzati is also notable in terms of its particular architecture, built in the first decades of the eighteenth century by Francesco Bernardi, called the Senesino, a castrated lyrical singer, a sopranist who became famous in Europe almost like Farinelli. Character we talk about in another of our itineraries. As elsewhere, we tell of when Matilde and Vittoria Manzoni, daughters of Alessandro, lived at the Lizza. In a letter addressed to Matilde, the author of the Promessi sposi writes: «and I too run with my mind to the house that looks on the Lizza…».  Also regarding literary persons, in the plaque on the building at number 12 we can read: «The Daily vision of the cusps of the cathedral and the / Republican tower / gave to the verse of / Giovanni Marradi here guest / from 1897 to 1898 accents of winged / poetry and palpitations of freedom». Here, in fact, Marradi resided in the years when he taught in Siena. And in the rooms that in the distance saw the cusps of the Cathedral and the Torre del Mangia, he composed the Sienese Epistle dedicated to pastures: «or that blooms, or pastures, every summit / of the beautiful Sienese hills and in pink focus / light the sunsets, or your delight / loneliness leave for a little, / and come to me. My house waits for you / and you set up a lovely place, / here where to you, thoughtful trovadore, / Siena, city of Dreams, opens its core». The invitation in verse goes on saying: «You will see from my house, on a lot of history / mute in the stone of the archigni castles, / the cusps of the Duomo (Hymn of glory / that raised to Mary the sanguine ancestors) / stand out in the sky with agile victory / almost candid flying wings of swans, / and a silvery Ray burn each / in the mystical silence of the moon». It does not appear that Pascoli has accepted the poetic invitation. However, he had already been to Siena a few years earlier, in August 1892, as commissioner of examination, and in a letter addressed to the sisters wrote that Siena was beautiful, but he could not live there “not even painted” , he would miss too much the air of the countryside.

Also regarding literary persons, in the plaque on the building at number 12 we can read: «The Daily vision of the cusps of the cathedral and the / Republican tower / gave to the verse of / Giovanni Marradi here guest / from 1897 to 1898 accents of winged / poetry and palpitations of freedom». Here, in fact, Marradi resided in the years when he taught in Siena. And in the rooms that in the distance saw the cusps of the Cathedral and the Torre del Mangia, he composed the Sienese Epistle dedicated to pastures: «or that blooms, or pastures, every summit / of the beautiful Sienese hills and in pink focus / light the sunsets, or your delight / loneliness leave for a little, / and come to me. My house waits for you / and you set up a lovely place, / here where to you, thoughtful trovadore, / Siena, city of Dreams, opens its core». The invitation in verse goes on saying: «You will see from my house, on a lot of history / mute in the stone of the archigni castles, / the cusps of the Duomo (Hymn of glory / that raised to Mary the sanguine ancestors) / stand out in the sky with agile victory / almost candid flying wings of swans, / and a silvery Ray burn each / in the mystical silence of the moon». It does not appear that Pascoli has accepted the poetic invitation. However, he had already been to Siena a few years earlier, in August 1892, as commissioner of examination, and in a letter addressed to the sisters wrote that Siena was beautiful, but he could not live there “not even painted” , he would miss too much the air of the countryside.

The serene peace of a kindergarten

The Lizza is, in some respects, a place of memory. Whole generations played there as children, it was walked through by lovers, and parents and grandparents sat on its benches. Not far from the pool where a white swan dominates between fish and ducks, we find, vividly depicted, the spirit of the place, which is transmitted from one generation to another: it is enclosed in the sculpture of the Horse and her foal by Sandro Chia (1994), in which a foal is still uncertain on his legs, and so leans towards the adult horse. And this is also a place of dramatic memories, as dramatic was the Great War, which is recalled here (on the side of viale Franci, at number 26) with an unequivocal symbol of peace. When, in 1919, monuments were erected everywhere to honour the memory of the fallen in the war, the municipality of Siena believed that there could not be more significant testimony than a building to be used for childhood.  It was thus decided to build what was immediately known as an Asilo Monumento (childhood monument). It was designed by the architect Vittorio Mariani, who in previous years had already built the palazzo delle Poste and the Chamber of Commerce (this last building no longer exists). The inauguration took place on September 28, 1924 in the Asilo Monumento presence of King Vittorio Emanuele III. Piero Calamandrei, then a young professor at the University of Siena, gave the official speech. In a very intense of his speech, he said: «No ceremony will tell them [the war dead] the devotion of the survivors, as the peace and the calm of this asylum, in which they will not find the noisy gatherings that disturb the collection of the humility of death or the empty rants of the rhetoricians who left others to die in silence, but the choirs joyful of the children who sing, dance and still do not know how many tears and how much blood the dead have given to create the happiness of those who remained». Even today, the voices of kindergarten children resonate within those walls. Let us take a step back in time by reading the erected stone outside the kindergarten gate. It reminds us that on this area, during the Spanish occupation of the mid-sixteenth century, Diego Hurtado de Mendoza, by Order of Charles V, had built a fortified citadel. When the Sienese, on August 4, 1552, managed, with the help of the French, to drive the imperial garrison out of the city, the fortress was destroyed to the fury of the people. The Diary of Alessandro Sozzini, written in 1587, provides an accurate description of the event that involved the whole city. The huge procession consisted of «the Lordship, the Captain of the people, with all of the Orders and the rulers, and explained next to their Lordships the standard of Our Woman, and they all, with wreaths at the head of green olive, andorno of the said citadel, with the greatest multitude of people, with the procession of all the clergy, with many in the company with zapponi, picks, hammers, stakes of iron and other tools for spoil; seemed that everyone went to the wedding. The captain of the people and the illustrious gentlemen with picks and other instruments began to ruin the Citadel and all the people cried, with tears in their eyes for joy: freedom, freedom; France, France; victory, victory … but in the space of an hour there was so much ruin towards the city, that it would not be walled in four months».

It was thus decided to build what was immediately known as an Asilo Monumento (childhood monument). It was designed by the architect Vittorio Mariani, who in previous years had already built the palazzo delle Poste and the Chamber of Commerce (this last building no longer exists). The inauguration took place on September 28, 1924 in the Asilo Monumento presence of King Vittorio Emanuele III. Piero Calamandrei, then a young professor at the University of Siena, gave the official speech. In a very intense of his speech, he said: «No ceremony will tell them [the war dead] the devotion of the survivors, as the peace and the calm of this asylum, in which they will not find the noisy gatherings that disturb the collection of the humility of death or the empty rants of the rhetoricians who left others to die in silence, but the choirs joyful of the children who sing, dance and still do not know how many tears and how much blood the dead have given to create the happiness of those who remained». Even today, the voices of kindergarten children resonate within those walls. Let us take a step back in time by reading the erected stone outside the kindergarten gate. It reminds us that on this area, during the Spanish occupation of the mid-sixteenth century, Diego Hurtado de Mendoza, by Order of Charles V, had built a fortified citadel. When the Sienese, on August 4, 1552, managed, with the help of the French, to drive the imperial garrison out of the city, the fortress was destroyed to the fury of the people. The Diary of Alessandro Sozzini, written in 1587, provides an accurate description of the event that involved the whole city. The huge procession consisted of «the Lordship, the Captain of the people, with all of the Orders and the rulers, and explained next to their Lordships the standard of Our Woman, and they all, with wreaths at the head of green olive, andorno of the said citadel, with the greatest multitude of people, with the procession of all the clergy, with many in the company with zapponi, picks, hammers, stakes of iron and other tools for spoil; seemed that everyone went to the wedding. The captain of the people and the illustrious gentlemen with picks and other instruments began to ruin the Citadel and all the people cried, with tears in their eyes for joy: freedom, freedom; France, France; victory, victory … but in the space of an hour there was so much ruin towards the city, that it would not be walled in four months».

La Fortezza dei Medici

We leave the Lizza gardens to move to the nearby Forte Santa Barbara the Medici fortress, whose name suggests another domination to which the Sienese had to reluctantly submit. That of the Medici, when, after the fall of the Republic of Siena in 1555, Siena was also annexed to the Grand Duchy of Tuscany. The Fortress was erected in 1561 by Cosimo I (defined by the Sienese, “the Medici thief”) based on the design of the military architect Baldassarre Lanci of Urbino. It is a powerful rectangular brick construction enclosing four bastions at the corners called San Filippo, la Madonna, San Domenico, San Francesco or Dell’amore. The Medici dynasty (the last was Gian Gastone who died in 1737) was extinguished. Among them was Pietro Leopoldo (succeeded his father Francesco Stefano), who began a program of wide- ranging reforms, restoring Tuscany to a modern dignified state and, in several respects, to the avant- garde (just think of the abolition of the death penalty promulgated in 1786). Not all the leopoldine reforms were liked by the Sienese. Among these the liberalization of the wheat trade even beyond the borders which caused bread prices to rise, so much so as to infuriate the people who flaunted the best of the turpiloquy at the address of Leopold. Although on a diet for less bread, the Sienese citizens earned, however, the chance to breathe good air on the ramparts of the Fortress. The Grand Duke, in fact, had the fortress transformed from a military structure to public gardens designed by the architect Antonio Matteucci and made by Leopoldo Prucker, gardener of the same Grand Duke. They were inaugurated in 1779.  On this occasion, the Sienese wanted to show gratitude to Leopold by erecting a monument inside the fortress, but he opposed it. A plaque was then placed at the entrance with the inscription: «The Austrian Pietro Leopoldo, given the loyalty of the Sienese, changed into delight, in the year 1778, the fortress built by Cosimo de ‘Medici for the safety of his command in the year 1561». In 1937, the ramparts were further arranged for walking. It is therefore thanks to Pietro Leopoldo that the city, even today, enjoys this undoubtedly evocative space. And it is not by chance that the fortress has become, over time, also a sort of literary park, as it is mentioned in pages of important authors. The already remembered Henry James, often together with his writer friend Paul Bourget (both were staying at the Grand Hotel Royal), loved to walk on the ramparts of the fortress and gaze out over the horizon. In his book Italian Hours (1909) we read: «[…] A long-term horizon, strange, melancholic, beautiful, edge of distant mountains that paint, for those who leans, towards the hour of sunset, from the old parapets, smooth and shine to the use, a country not exactly arid and desert, but which has taken on a life on a scale so immense, and he retired, with all his memories and his relics, in a shelter rather austere, in fact almost dark, and inhuman. Anyway, that was a condition, a state of mind, spread all over the place, that favoured, in the late afternoon, the blue and the purple the most divine in the landscape, not to mention the fact that so favoured, even to a greater extent, my real belief according to which the whole fortified mountain, with its huge buttresses by the golden hues of red and brown, sunk perpendicular to the road within the vineyards, orchards, wheat fields, and all that rustic elegance that characterizes the Tuscan farmhouse, the same weaving for me a crown of unforgettable hours […]». Vernon Lee (English writer who died in Florence in 1935 and author of the book Genius loci: the spirit of places) noted: «the subtle piercing of the blue overseas of those hills beyond the Lizza […]; that unmistakable blue color against the Eburne sky of the evening was identified and even became, so to speak, the very colour of the desire of the inaccessible, of the discharge which it has too briefly enjoyed». From the bastion facing the town, the British poet Arthur Symons (1865-1945) admired thus the panorama: «From the fortifications you can see the entire city, the houses are brown and white, with a roof brown and the façade, smooth, perforated by many windows, that stand side by side, one above the other, with no space visible in the middle; so grouped, almost for the sake of safety, or perhaps as a sign of friendliness, climb up the long and narrow construction of the Cathedral, surmounted by a dome and tower, it seems to melt the whole of this irregular mass in a single harmony». It will be on this same scenario that the Sienese writer Federigo Tozzi initiates the epilogue of his novel Tre croci, a dramatic story of family economic collapse, misery and mourning: «[…] It took him to look at Siena; from the shoulder of the Fortress. He said «come and see how, at this hour, the colors are more beautiful than the evening. I convinced myself by coming here in the morning and in the day». A large bulge of houses is immediately visible; and, inside, the Cathedral. In Fontebranda, the houses instead bifurcate, leaving an empty space in the middle. They stand as if attacked and crushed under the cathedral; overhanging the gardens and the countryside. Then they lower more and more until they disappear, under a ledge; and then you can only see their roofs. The larger ones hold the other; and it is not possible to understand where the streets are; because the houses seem to be separated from each other by cracks and cuts almost bizarre, in bulk; to crossbows, opposite, of all lengths and all species. And the roofs, in those spades and in those recesses, in those fragments of every form, are increasingly rare from hand to hand that the houses are scattered around the slopes. The campaign was of a magnitude that never ended; and Siena, in that silence, almost taciturn but gentle, seemed all gathered unto itself and unapproachable. While the farthest peaks, up to the Cornate of Gerfalco, skidded and filled the lost horizon. Giulio looked greedily: «he had never loved his Siena as he did then; and he was proud of it». Just commenting on the scenarios that Tozzi poses as the backdrop to some of his pages setting of siena, Carlo Cassola emphasized: «Siena is not very high and not even on an isolated hill; but the hills around are almost all low, and thus, the view sweeps freely in every direction, towards the Hillock, towards the Chianti, to the Amiata to the hills of the Maremma. Especially in the evening, when the subsequent undulations of the countryside and the mountainous horizon darken, from those distances comes a sense of cold and loneliness». To Giovanni Comisso, the city seen from here appears, instead, as a ship in the instant of detaching itself from the pier: «it was pleasant to walk on the ramparts of the fortress, from there you could see all the swaying of the slopes, now reddish, now yellow, interrupted by spots of cypresses or by deep gullies. Far towards midday, the horizon is limited by the blue mountains of the Maremma, and the sky from all over arching dry and light. The city with its towers and churches rises alongside on the back of the hill and in the evening lights up at every window like a steamer ready to go». A nocturnal atmosphere of the Fortress is offered in a poem by Carlo Betocchi (double Serenade in Siena) where, with the song of the chiù and in the light of the moon, «… I looked at the stocky / houses, large and black, / make nightly weddings / for the lightened windows». And also Leonardo Sciascia, with a poet’s pen, remembers: «Siena. At the fortress young people / with big dogs on a leash, / girls in spring robes. / And the furious music of the funfair / is sweet with magnolias…».

On this occasion, the Sienese wanted to show gratitude to Leopold by erecting a monument inside the fortress, but he opposed it. A plaque was then placed at the entrance with the inscription: «The Austrian Pietro Leopoldo, given the loyalty of the Sienese, changed into delight, in the year 1778, the fortress built by Cosimo de ‘Medici for the safety of his command in the year 1561». In 1937, the ramparts were further arranged for walking. It is therefore thanks to Pietro Leopoldo that the city, even today, enjoys this undoubtedly evocative space. And it is not by chance that the fortress has become, over time, also a sort of literary park, as it is mentioned in pages of important authors. The already remembered Henry James, often together with his writer friend Paul Bourget (both were staying at the Grand Hotel Royal), loved to walk on the ramparts of the fortress and gaze out over the horizon. In his book Italian Hours (1909) we read: «[…] A long-term horizon, strange, melancholic, beautiful, edge of distant mountains that paint, for those who leans, towards the hour of sunset, from the old parapets, smooth and shine to the use, a country not exactly arid and desert, but which has taken on a life on a scale so immense, and he retired, with all his memories and his relics, in a shelter rather austere, in fact almost dark, and inhuman. Anyway, that was a condition, a state of mind, spread all over the place, that favoured, in the late afternoon, the blue and the purple the most divine in the landscape, not to mention the fact that so favoured, even to a greater extent, my real belief according to which the whole fortified mountain, with its huge buttresses by the golden hues of red and brown, sunk perpendicular to the road within the vineyards, orchards, wheat fields, and all that rustic elegance that characterizes the Tuscan farmhouse, the same weaving for me a crown of unforgettable hours […]». Vernon Lee (English writer who died in Florence in 1935 and author of the book Genius loci: the spirit of places) noted: «the subtle piercing of the blue overseas of those hills beyond the Lizza […]; that unmistakable blue color against the Eburne sky of the evening was identified and even became, so to speak, the very colour of the desire of the inaccessible, of the discharge which it has too briefly enjoyed». From the bastion facing the town, the British poet Arthur Symons (1865-1945) admired thus the panorama: «From the fortifications you can see the entire city, the houses are brown and white, with a roof brown and the façade, smooth, perforated by many windows, that stand side by side, one above the other, with no space visible in the middle; so grouped, almost for the sake of safety, or perhaps as a sign of friendliness, climb up the long and narrow construction of the Cathedral, surmounted by a dome and tower, it seems to melt the whole of this irregular mass in a single harmony». It will be on this same scenario that the Sienese writer Federigo Tozzi initiates the epilogue of his novel Tre croci, a dramatic story of family economic collapse, misery and mourning: «[…] It took him to look at Siena; from the shoulder of the Fortress. He said «come and see how, at this hour, the colors are more beautiful than the evening. I convinced myself by coming here in the morning and in the day». A large bulge of houses is immediately visible; and, inside, the Cathedral. In Fontebranda, the houses instead bifurcate, leaving an empty space in the middle. They stand as if attacked and crushed under the cathedral; overhanging the gardens and the countryside. Then they lower more and more until they disappear, under a ledge; and then you can only see their roofs. The larger ones hold the other; and it is not possible to understand where the streets are; because the houses seem to be separated from each other by cracks and cuts almost bizarre, in bulk; to crossbows, opposite, of all lengths and all species. And the roofs, in those spades and in those recesses, in those fragments of every form, are increasingly rare from hand to hand that the houses are scattered around the slopes. The campaign was of a magnitude that never ended; and Siena, in that silence, almost taciturn but gentle, seemed all gathered unto itself and unapproachable. While the farthest peaks, up to the Cornate of Gerfalco, skidded and filled the lost horizon. Giulio looked greedily: «he had never loved his Siena as he did then; and he was proud of it». Just commenting on the scenarios that Tozzi poses as the backdrop to some of his pages setting of siena, Carlo Cassola emphasized: «Siena is not very high and not even on an isolated hill; but the hills around are almost all low, and thus, the view sweeps freely in every direction, towards the Hillock, towards the Chianti, to the Amiata to the hills of the Maremma. Especially in the evening, when the subsequent undulations of the countryside and the mountainous horizon darken, from those distances comes a sense of cold and loneliness». To Giovanni Comisso, the city seen from here appears, instead, as a ship in the instant of detaching itself from the pier: «it was pleasant to walk on the ramparts of the fortress, from there you could see all the swaying of the slopes, now reddish, now yellow, interrupted by spots of cypresses or by deep gullies. Far towards midday, the horizon is limited by the blue mountains of the Maremma, and the sky from all over arching dry and light. The city with its towers and churches rises alongside on the back of the hill and in the evening lights up at every window like a steamer ready to go». A nocturnal atmosphere of the Fortress is offered in a poem by Carlo Betocchi (double Serenade in Siena) where, with the song of the chiù and in the light of the moon, «… I looked at the stocky / houses, large and black, / make nightly weddings / for the lightened windows». And also Leonardo Sciascia, with a poet’s pen, remembers: «Siena. At the fortress young people / with big dogs on a leash, / girls in spring robes. / And the furious music of the funfair / is sweet with magnolias…».  In August 1935, the fortress was the scene of the “Mostra Mercato dei Vini tipici d’italia” (a first edition took place there in 1933). In this context, a competition of “bacchica poetry amorous and warrior” was organized with jury president Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, founding father of futurism. In this regard, there is a witty testimony by Mario Verdone-at the time eighteen year old aspiring journalist – where we learn that Lorenzo Viani was the first prize winner with the verses entitled “Sarabanda del vino”. In the dinner that followed the award ceremony – Verdone says – the winning poet was invited to reclaim his poetry again. Viani, therefore, «climbed on a table between uncapped bottles and semi-full cups, napkins stained with Chianti and tomato and said it with little eyes that sparkled and laughed, while everything around was a continuous feast». It is also said that in this euphoric climate, Marinetti went to shout in pure futuristic style: «Brunello is gasoline!», alluding – let it be clear – certainly not to the taste of the fine Montalcino wine, but to what sets in motion its delicacy. Marinetti’s presence had meant that several other sympathizers of the Futurist movement had intervened in the initiative. That evening, in the fortress, Luciano Folgore, Lorenzo Ercole Lanza, Bino Sanminiatelli, Farfa (Vittorio Osvaldo Tommasini), Krimer (Cristoforo Mercati), Virgilio Marchi were seen to raise the glasses loudly. The latter, theorist of the new architecture of the ‘futuristic city’ , had also collaborated in setting up the exhibition spaces for the show.

In August 1935, the fortress was the scene of the “Mostra Mercato dei Vini tipici d’italia” (a first edition took place there in 1933). In this context, a competition of “bacchica poetry amorous and warrior” was organized with jury president Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, founding father of futurism. In this regard, there is a witty testimony by Mario Verdone-at the time eighteen year old aspiring journalist – where we learn that Lorenzo Viani was the first prize winner with the verses entitled “Sarabanda del vino”. In the dinner that followed the award ceremony – Verdone says – the winning poet was invited to reclaim his poetry again. Viani, therefore, «climbed on a table between uncapped bottles and semi-full cups, napkins stained with Chianti and tomato and said it with little eyes that sparkled and laughed, while everything around was a continuous feast». It is also said that in this euphoric climate, Marinetti went to shout in pure futuristic style: «Brunello is gasoline!», alluding – let it be clear – certainly not to the taste of the fine Montalcino wine, but to what sets in motion its delicacy. Marinetti’s presence had meant that several other sympathizers of the Futurist movement had intervened in the initiative. That evening, in the fortress, Luciano Folgore, Lorenzo Ercole Lanza, Bino Sanminiatelli, Farfa (Vittorio Osvaldo Tommasini), Krimer (Cristoforo Mercati), Virgilio Marchi were seen to raise the glasses loudly. The latter, theorist of the new architecture of the ‘futuristic city’ , had also collaborated in setting up the exhibition spaces for the show.

As in a vision

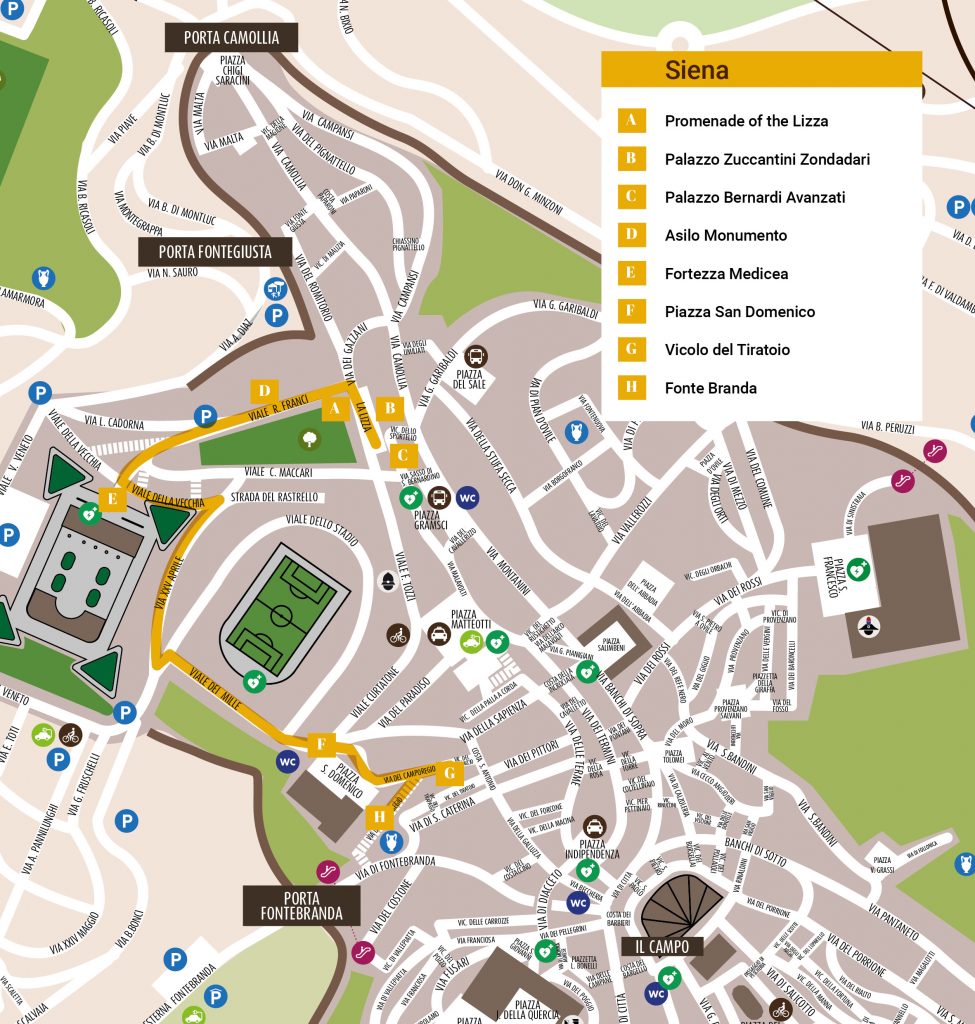

We leave the Fortress. On the right, we follow the vialetto della Lizza until we turn into viale XXV Aprile and then, on the left, into viale dei Mille, thus finding ourselves in the square of San Domenico in front of another vision of the city which, in fact, can be defined more as a vision than seen. From here the city seems unreal, however beautiful and perfect it looks. It seems like one of The “Invisible Cities” recounted by Italo Calvino. Maybe precisely the city of which, according to the writer, one could say «how many steps in the stairwayed streets, of which sixth the arches of the arcades». However – the narrator warned – it would be like saying nothing, because «this is not what the city is made of, but of relations between the measures of its space and the events of its past». But you know as well that «the city does not tell its past», rather, «but contains it like the lines of a hand, written in the corners of the streets, the gratings of the windows, in the turn of the stairs, in the antennae of the lightning rods, in the rods of the flags, every segment lined in turn with scratches, jagged, notched, commas». The anthology would be really full-bodied if we were to quote all the literary pages describing this view of the city. The theme of dreams and enchantment often recurs. The unpredictable geometries of the buildings are fascinating, the shadows of the streets, the vision of the houses that-Symons wrote – ” climb up the fence, piling, or rather, tightening around the cathedral until the roofs and walls merge with its structure.» From via Camporegio, through the tube of the vicolo Del Campaccio (but not without taking a last look at the huge volume of san Domenico) you reach the Costa di Sant’antonio and, descending the few stairs to the right, the vicolo del Tiratoio. So called because the “domus tiratorium” stood there in the fourteenth century, the place where cloth pieces from processing were laid out to dry on special tensioners (tiratoi). A building used as a fulling mill was built here in 1344 by the Arte della Lana (the corporation which grouped together the fabric manufacturers). Largely modified over the centuries, the building can be seen along the last stretch of the alley, which takes us to Fonte Branda.

The whispering water

Strict and refined, with the three large ogival arches surmounted by battlements, Fonte Branda has been remembered since 1081. It was rebuilt in bricks, in the current forms, by Giovanni Di Stefano in 1246. Originally it was formed by three tanks: the first for drinking water; the second, fed by the neighbour’s overflow, for animal drinking water; the third used as a washing machine. The resultsing waters were used by tanners, dry cleaners, and many wool workshops operating in the area. Among the gossip punctually reported in travellers’ notebook, we can mention the devastating effects attributed to the water of Fonte Branda for anyone who drank it, and who became crazy. A different and more reassuring version tells, instead, of a spell: once thirst is quenched under those vaults, nothing could take us away from Siena. If you have a chance to come at night, the atmosphere is bewitching. This was experienced by the Danish writer Johannes Joergens, who in a poetic prose says that Fonte Branda is “talking”, with its «sound of water, of deep and dark water/sound of water, / that sways and gurgles, whispers, gobbles and whines». On a night in which «the wind stirred three cypresses around the wall of San Domenico», Guido Ceronetti also came down here to live – as we read in his Viaggio in Italia – a pure moment at midnight, near the water of Fontebranda». So, try to believe.

Produced by: toscanalibri.it

Texts edited by: Luigi Oliveto

Editorial coordination: Elisa Boniello e Laura Modafferi

Photos: Archivio Comune di Siena

Graphic design: Michela Bracciali