2.3 The neighborhood of miracles and the valle dei rozzi

Harlots, soldiers and fervent Christians

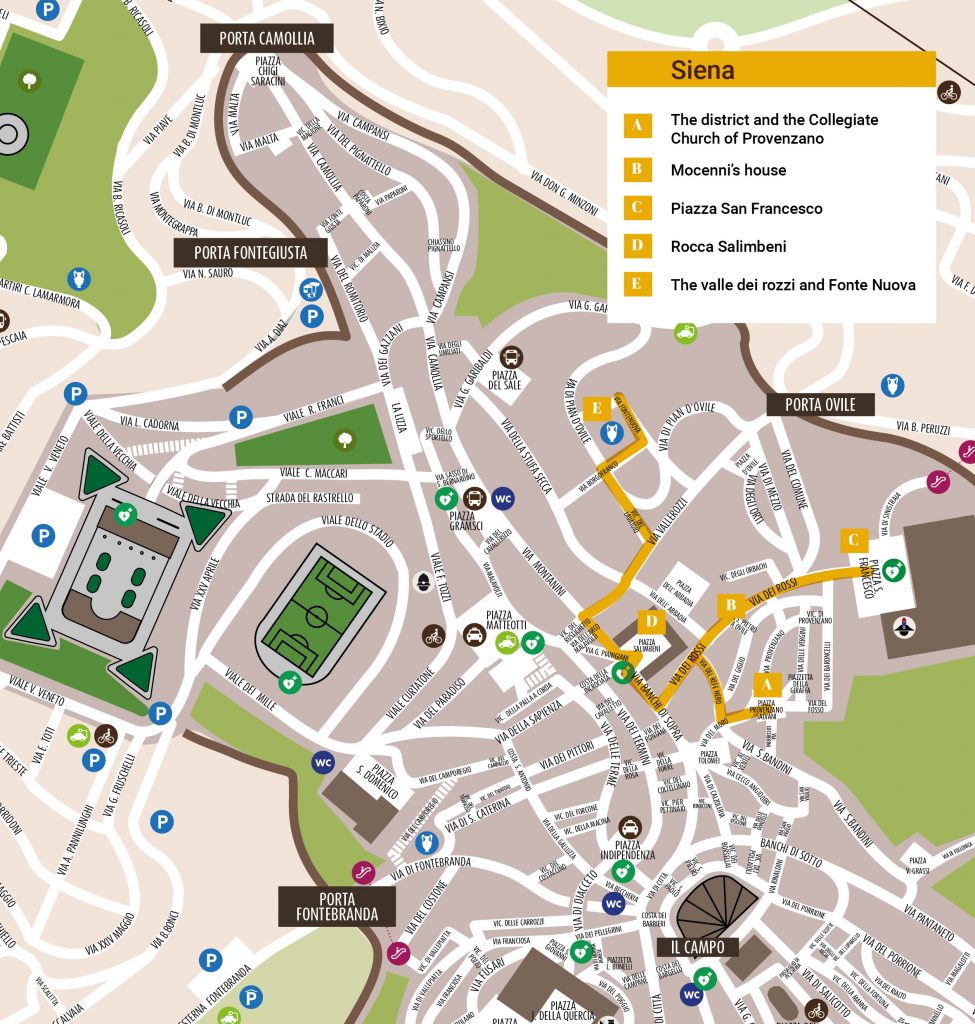

The piazza Provenzano Salvani, built within an area where the Salvani owned lands and buildings in medieval times, bears the name of most famous member of the noble house. Provenzano, in fact, the leader born in Siena around 1220 and died in battle at Colle Di Valdelsa in 1269. He was the son of Ildebrandino and grandson of Sapia, a Sienese gentlewoman of the opposite Guelph faction. In the sixteenth century, the area that today is called simply ‘Provenzano’, was known for the many prostitutes who exercised their profession there. Ironic testimony to this remains even in the street names. We have, for example, via delle Vergini; or an alley named after a certain Viola, whose professionalism must have been so appreciated that it deserves the dedication of a road. These trades reached figures of economic miracle in the mid-sixteenth century, at the time of Spanish domination, thanks to the soldiers of Don Diego Hurtado of Mendoza, who from the nearby convent of San Francesco, where they were garrisoned, could easily reach the Case delle señoritas. It should be remembered, in this regard, that the Republic of Siena also found itself involved in the Franco-Spanish Italian wars (1494-1559). So much so that, in 1551, Charles V sent to Siena his representative, Don Diego Hurtado de Mendoza, to establish a permanent protectorate in Sienese land. Indeed a fortified citadel was built, but this interference did not please the Sienese who, with a popular uprising (July 26, 1552) opened the doors to the French and, together, managed to confine the Spaniards in the fortress they had built, until they drove them out of the city.

But the time has come to tell how the (red) lights of the catapecchias of the Provenzano district would have dimmed in the sparkle of an imposing temple, the Collegiate Church of Santa Maria Di Provenzano. Between history and legend, this happened. Near the Collegiate Church, on the facade of one of those infamous houses, there was a newsstand depicting a small terracotta Pietà. Just at the time of the Spanish occupation, a soldier, drunk and in the mood for bravado, shot an arquebus at the tabernacle. The blow shattered the entire lower part of the statue and the treacherous person died from the weapon’s implosion (according to other versions survived and felt he had to convert).  Thus only the face and the bust of the image of the Virgin remained. Those remains became the destination for often answered reparative prayers and graces, to the point when in 1594 it was decided to build a large church to preserve the sacred image that the ecclesiastical authority had decreed ‘miraculous’. On October 23, 1611, with a solemn procession through the streets of the city, the bust of Our Lady entered the new sanctuary dedicated to her which in 1634 Pope Urban VIII would have elevated to a distinguished collegiate establishing a chapter of Canons presided by a proposed. Already in 1614, the Grand Duke of Tuscany, to manage the huge flow of pilgrims, had founded the Opera of Santa Maria in Provenzano, presided over by a secular rector, appointed by the city institutions. In the chapter hall of the Collegiate Church, there is what could be called a vintage photo. A canvas by Antonio Di Taddeo Gregori depicting the Procession for the translation of the Madonna inside the sanctuary. It is, however, an interesting topographic testimony of the city of that time. With the temple built, the harlots-except for some who were on the way to redemption-considered it appropriate to move elsewhere. An emphatic summary of the events related to the’ healing ‘ of the ward is written in Latin on the side of the church along via Provenzano Salvani. On the plaque, placed in 1723 by the Knight Alcibiade Lucarini Bellanti, rector of the Church of Provenzano, we read: «Stop a little wanderer, as long as the image of the Blessed Virgin Mary does not go unnoticed here. This whole area of Provenzano was exposed to Harlots, but after the Virgin star flashed dissolved like fog that plague, the lupanare from here disappeared and, coming from every side the Sienese devotion, was erected the very near Church where the sacred image is venerated by a great influx of peoples».

Thus only the face and the bust of the image of the Virgin remained. Those remains became the destination for often answered reparative prayers and graces, to the point when in 1594 it was decided to build a large church to preserve the sacred image that the ecclesiastical authority had decreed ‘miraculous’. On October 23, 1611, with a solemn procession through the streets of the city, the bust of Our Lady entered the new sanctuary dedicated to her which in 1634 Pope Urban VIII would have elevated to a distinguished collegiate establishing a chapter of Canons presided by a proposed. Already in 1614, the Grand Duke of Tuscany, to manage the huge flow of pilgrims, had founded the Opera of Santa Maria in Provenzano, presided over by a secular rector, appointed by the city institutions. In the chapter hall of the Collegiate Church, there is what could be called a vintage photo. A canvas by Antonio Di Taddeo Gregori depicting the Procession for the translation of the Madonna inside the sanctuary. It is, however, an interesting topographic testimony of the city of that time. With the temple built, the harlots-except for some who were on the way to redemption-considered it appropriate to move elsewhere. An emphatic summary of the events related to the’ healing ‘ of the ward is written in Latin on the side of the church along via Provenzano Salvani. On the plaque, placed in 1723 by the Knight Alcibiade Lucarini Bellanti, rector of the Church of Provenzano, we read: «Stop a little wanderer, as long as the image of the Blessed Virgin Mary does not go unnoticed here. This whole area of Provenzano was exposed to Harlots, but after the Virgin star flashed dissolved like fog that plague, the lupanare from here disappeared and, coming from every side the Sienese devotion, was erected the very near Church where the sacred image is venerated by a great influx of peoples».

The temple, in fact, was immediately a fulcrum of devotion, not only of the people but also of nobles. Above all, the Medici governors, whom the building of the church had substantially financed. Caterina de ‘ Medici, Governor of Siena from 1627 to 1629, arranged, before her death, that her heart be buried in Provenzano as a pledge of the devotion she nurtured for that Madonna. And the entrails of Prince Mattias, who died on October 11, 1667, were buried in the Sienese Collegiate Church. Veneration for Our Lady of Provenzano was of further importance when, in 1656, it was established that in her honour, every 2 July (according to the extraordinary form of the liturgical calendar, feast of the visitation of the Blessed Virgin Mary after which the Collegiate Church is named) a palio “alla tonda” would be held (running, that is, along the Outer Ring of Piazza del Campo).  It was an important decision for the history of the palio di Siena, since, in this way, he went to codify a regular cadence and explicit dedication to Our Lady. On summer days, when the marble of the Collegiate Church reverberates light and memory, the square seems to flood with a metaphysical solitude. Only the days of the Palio seem to lead it back to a concrete measure, populating it with colours, of sweaty humanity. Alongside the cathedral, this place constitutes the other pole of Marian worship, famously rooted in Siena for its atavic heritage, so much so the city is called “Civitas Virginis”. Hence also the reason for the two Pali dedicated to Our Lady: the Assumed, invoked in the Gothic slants of the cathedral; the one, in the appearance of fragile terracotta, prayed, precisely, in the collegiate church of Provenzano.

It was an important decision for the history of the palio di Siena, since, in this way, he went to codify a regular cadence and explicit dedication to Our Lady. On summer days, when the marble of the Collegiate Church reverberates light and memory, the square seems to flood with a metaphysical solitude. Only the days of the Palio seem to lead it back to a concrete measure, populating it with colours, of sweaty humanity. Alongside the cathedral, this place constitutes the other pole of Marian worship, famously rooted in Siena for its atavic heritage, so much so the city is called “Civitas Virginis”. Hence also the reason for the two Pali dedicated to Our Lady: the Assumed, invoked in the Gothic slants of the cathedral; the one, in the appearance of fragile terracotta, prayed, precisely, in the collegiate church of Provenzano.

A literary salon

In via dei Rossi, on the facade of the building at number 104, we learn from a plaque that «Vittorio Alfieri and Francesco Gianni, frequented this house, dear one, having the friendship of Teresa Regoli Mocenni». An information that recalls the years of the late eighteenth century, when numerous salons arose in Siena as well, where people would meet to discuss politics, philosophy, literature; and, no less, to gossip or concoct and cultivate love affairs. Among the most famous salons or parlours, we can mention Casa Regoli Mocenni, which Teresa animated with enthusiasm and a tad of rudeness. It was called The ‘Yellow Venus ‘ for its ill-fated face and dull colour. She had married, very young, the rich merchant Ansano Mocenni, a grumpy man, not at all inclined to attend salons, not even that of his own house where his wife received acculturated people in the mood for chatter.  Among them Teresa’s favorite was Mario Bianchi Bandinelli, and in fact it was rumored that he was her lover. The plate goes on to cite two names: Francesco Maria Gianni, a Florentine economist, minister of the grand duke Pietro Leopoldo, who was in Siena to study a reform of the Magistrate of the Abundance and run an analytic census on the state of the economy of Siena; and the more famous Vittorio Alfieri, who had a great friend in Siena, Francesco Gori Gandellini, and with whom he stayed as a guest for several months in 1777. It was Gori in fact who introduced Alfieri into the circle of the associates from the Salotto Mocenni, defined by Alfieri himself a «criss cross of six or seven individuals endowed with a sense, judgment, taste and culture, not to be believed in such a small country». In a sonnet, the poet censors almost all of them: «two Gori, one Bianchi and half an archpriest. / A beautiful Carlotta, and cocciutina; / a kind Teresa, and a little ‘ Nina, / make it so I find a peace in Siena». Count Alfieri – at the time a handsome and intriguing twenty – eight-year- old-was not insensitive to female charm, and even in Siena he did his best. The Nina who in the sonnet is mentioned as escaped had an overwhelming love affair with the poet. It was Caterina Gori Zondadari, wife of Francesco Zondadari and mother of two children. It is to her that Alfieri, once left Siena, will write a letter calling her “Nina mia dolcissima Padrona” and recommending: «let me know when you go to the villa: to whom I can write so that letters do not happen to other hands than yours. I feel a canonical sense to be the easiest means, if you want to do it». The canon in question was the archpriest Ansano Luti, frequenter of casa Mocenni and not by chance mentioned in the alfierian sonnet. The letter has heartfelt tones:«know that you are as dear to me as life, but much less than fame. That I am gone, that I will not love you too much, and that I will never forget you». Then there is a Sibylline phrase: «I recommend to you that city, which if not mine, at least was created under my auspices». The “city” referred to would be the third son of Catherine who was born in 1778. The coincidence was not lost on the mischievous regulars at the Mocenni salon: the creature had come into the world exactly nine months since Alfieri had arrived in the city of the Palio.

Among them Teresa’s favorite was Mario Bianchi Bandinelli, and in fact it was rumored that he was her lover. The plate goes on to cite two names: Francesco Maria Gianni, a Florentine economist, minister of the grand duke Pietro Leopoldo, who was in Siena to study a reform of the Magistrate of the Abundance and run an analytic census on the state of the economy of Siena; and the more famous Vittorio Alfieri, who had a great friend in Siena, Francesco Gori Gandellini, and with whom he stayed as a guest for several months in 1777. It was Gori in fact who introduced Alfieri into the circle of the associates from the Salotto Mocenni, defined by Alfieri himself a «criss cross of six or seven individuals endowed with a sense, judgment, taste and culture, not to be believed in such a small country». In a sonnet, the poet censors almost all of them: «two Gori, one Bianchi and half an archpriest. / A beautiful Carlotta, and cocciutina; / a kind Teresa, and a little ‘ Nina, / make it so I find a peace in Siena». Count Alfieri – at the time a handsome and intriguing twenty – eight-year- old-was not insensitive to female charm, and even in Siena he did his best. The Nina who in the sonnet is mentioned as escaped had an overwhelming love affair with the poet. It was Caterina Gori Zondadari, wife of Francesco Zondadari and mother of two children. It is to her that Alfieri, once left Siena, will write a letter calling her “Nina mia dolcissima Padrona” and recommending: «let me know when you go to the villa: to whom I can write so that letters do not happen to other hands than yours. I feel a canonical sense to be the easiest means, if you want to do it». The canon in question was the archpriest Ansano Luti, frequenter of casa Mocenni and not by chance mentioned in the alfierian sonnet. The letter has heartfelt tones:«know that you are as dear to me as life, but much less than fame. That I am gone, that I will not love you too much, and that I will never forget you». Then there is a Sibylline phrase: «I recommend to you that city, which if not mine, at least was created under my auspices». The “city” referred to would be the third son of Catherine who was born in 1778. The coincidence was not lost on the mischievous regulars at the Mocenni salon: the creature had come into the world exactly nine months since Alfieri had arrived in the city of the Palio.

Here where the soul becomes sweet

Beyond the arch where via Dei Rossi ends, piazza San Francesco opens with the church of the same name in Gothic style started in 1326 and finished only in 1475 according to the probable design of Francesco Di Giorgio. Remodeled with baroque additions in the following centuries, it suffered a fire in 1655 and was restored, as we see it, between the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In this space of light and quiet, a page by Federigo Tozzi springs to mind where the Sienese writer notes that the main feeling transmitted by the square is sweetness. Such appears to him to be the vision of the roofs of the city leaning against each other, the fields of olive trees and vines, the church, the bell tower: «it is a sweetness that, if sometimes it seems tired, yet it feels even far away, among the green folds of the hills where I have never been». On the right is the oratory named after San Bernardino (1380-1444), because the friar gave his raging sermons even in this square. On the facade of the sixteenth century, there is the Bernardinian symbol: a sun with twelve rays and, in the centre, the three letters JHS, acronym of Jesus hominum salvator (Jesus saviour of men). The oratory is worth a visit for the works of art preserved inside, and which offer an interesting overview of Sienese painting from the thirteenth century. It can be considered a small museum of sacred art that revolves around the splendid upper chapel named after Santa Maria degli Angeli, completely frescoed at the beginning of the sixteenth century by Domenico Beccafumi, Giovanni Antonio Bazzi called the “Sodoma” and Girolamo Pacchia.  The entrance to the former Franciscan convent is in the corner of the square, and is now the university main office. The gate leads into the Renaissance cloister and, across the entire left side, we find stairs with eighteen carved coats of arms of the Tolomei. According to tradition, eighteen persons belonging to the noble house were buried here. Tradition has in fact perpetuated a story concerning the centuries-old feud between Tolomei and Salimbeni, in perennial struggle for political and economic issues. We are in the fourteenth century and it is said that the two powerful families, tired of the constant conflicts, had come to the decision to make peace. To seal the truce, the Salimbeni proposed to meet at a banquet on Easter Day in a location just outside the city. Eighteen representatives for each of the two houses took part, symbolically sitting alternately so that each Salimbeni would have a Tolomei next to them. The main dish was to be roast thrush, but, by the time it arrived at the table, the tray displayed only eighteen of the thirty-six little birds that should have been there. This did not escape the Tolomei, who argued that it was essential to obtain the thrush quickly so as not to have to share it with their neighbours. Sounding the invitation to start lunch, the head of the Salimbeni family shouted: «to each his own!» Each of the Tolomei rushed to put their thrush on the tray. Just as quickly, the Salimbeni, on the other hand, sank a knife into their respective neighbour at the table, a Tolomei in fact. Such was the peace that the Salimbeni had devised. The place where all this happened is located on the southern outskirts of the city, and is eloquently called Colle Di Malamerenda.

The entrance to the former Franciscan convent is in the corner of the square, and is now the university main office. The gate leads into the Renaissance cloister and, across the entire left side, we find stairs with eighteen carved coats of arms of the Tolomei. According to tradition, eighteen persons belonging to the noble house were buried here. Tradition has in fact perpetuated a story concerning the centuries-old feud between Tolomei and Salimbeni, in perennial struggle for political and economic issues. We are in the fourteenth century and it is said that the two powerful families, tired of the constant conflicts, had come to the decision to make peace. To seal the truce, the Salimbeni proposed to meet at a banquet on Easter Day in a location just outside the city. Eighteen representatives for each of the two houses took part, symbolically sitting alternately so that each Salimbeni would have a Tolomei next to them. The main dish was to be roast thrush, but, by the time it arrived at the table, the tray displayed only eighteen of the thirty-six little birds that should have been there. This did not escape the Tolomei, who argued that it was essential to obtain the thrush quickly so as not to have to share it with their neighbours. Sounding the invitation to start lunch, the head of the Salimbeni family shouted: «to each his own!» Each of the Tolomei rushed to put their thrush on the tray. Just as quickly, the Salimbeni, on the other hand, sank a knife into their respective neighbour at the table, a Tolomei in fact. Such was the peace that the Salimbeni had devised. The place where all this happened is located on the southern outskirts of the city, and is eloquently called Colle Di Malamerenda.  As for the burial of the eighteen victims in the stairwell of a church, many were sceptical that the prestigious Tolomei family had chosen such anonymous and modest tombs for their spouses. On the basis of the suggestions provided by Federigo Tozzi, we should now enter the great church: «One morning, indeed day, I entered the basilica of San Francesco; in Siena. The colours of the stained-glass windows were bruised, like pieces of ice, with the Saints numbed both within and across. [ … ] The frescoes of Lorenzetti were animated: all the Middle Ages were before me: I felt a sword in my hand, and firstly I had to start battles that lasted for centuries». The frescoes to which we allude are those of Ambrogio Lorenzetti (third Chapel of the left transept) depicting San Lodovico of Anjou at the foot of Boniface VIII and the Martyrs of Franciscans in Centa. Of particular beauty is the Crucifixion painted by Pietro Lorenzetti (first Chapel on the left of the presbytery), as well as the frescoes by Sassetta, Sodom, Lippo Vanni, Andrea Vanni. In the Cappella delle Sacre Particole (chapel of the sacred particles), we find preserved some hosts that on August 14, 1730 had been stolen along with a silver pyxid. The hosts were found after a few days in a box of alms in the collegiate of Provenzano. Subjected, over time to repeated scientific examinations, they show no signs of deterioration. The unnatural phenomenon was considered by the church a Eucharistic miracle, the so-called Miracle of the sacred particles. Leaving, next to the side door that on the right leads into the cloister of the current convent, you can notice a tombstone, placed on the floor, indicating (with a good dose of imagination) the Tomb of the legendary Pia de’ Tolomei.

As for the burial of the eighteen victims in the stairwell of a church, many were sceptical that the prestigious Tolomei family had chosen such anonymous and modest tombs for their spouses. On the basis of the suggestions provided by Federigo Tozzi, we should now enter the great church: «One morning, indeed day, I entered the basilica of San Francesco; in Siena. The colours of the stained-glass windows were bruised, like pieces of ice, with the Saints numbed both within and across. [ … ] The frescoes of Lorenzetti were animated: all the Middle Ages were before me: I felt a sword in my hand, and firstly I had to start battles that lasted for centuries». The frescoes to which we allude are those of Ambrogio Lorenzetti (third Chapel of the left transept) depicting San Lodovico of Anjou at the foot of Boniface VIII and the Martyrs of Franciscans in Centa. Of particular beauty is the Crucifixion painted by Pietro Lorenzetti (first Chapel on the left of the presbytery), as well as the frescoes by Sassetta, Sodom, Lippo Vanni, Andrea Vanni. In the Cappella delle Sacre Particole (chapel of the sacred particles), we find preserved some hosts that on August 14, 1730 had been stolen along with a silver pyxid. The hosts were found after a few days in a box of alms in the collegiate of Provenzano. Subjected, over time to repeated scientific examinations, they show no signs of deterioration. The unnatural phenomenon was considered by the church a Eucharistic miracle, the so-called Miracle of the sacred particles. Leaving, next to the side door that on the right leads into the cloister of the current convent, you can notice a tombstone, placed on the floor, indicating (with a good dose of imagination) the Tomb of the legendary Pia de’ Tolomei.

The Fortress of Salimbeni

We go up via Dei Rossi until we find, on the right, Via dell’Abbadia that leads to the square of the same name. Here we are reminded of the power of the Salimbeni in a concrete image via the massive tower that belonged to their castle, leaning, once, on the high-medieval walls near the Church of San Donato. This is the rear part (the one which best recalls its medieval origin) of the Palace remodeled in the nineteenth century in neo-Gothic style overlooking piazza Salimbeni, main office, since 1866, of the Monte dei Paschi bank. As already mentioned, the Salimbeni were one of the most relevant families in 13th and 14th century Siena.  Initially on the side of the Ghibellines, they exerted a strong political and economic influence. Owners of castles, palaces towers, they had accumulated wealth especially with the trade of wheat and spices in Maremma. The forerunner was considered a certain Giovanni lived in the thirteenth century, although they liked to say that their lineage descended from a certain Salimbene, who left in 1097 on the First Crusade with a contingent of a thousand Sienese led by Bonifazio Cricci. Also the following year, the legendary Salimbene would go back to conquer Antioch ,of which he would later be appointed patriarch, but he did refuse the office. In 1419, the Sienese Republic confiscated the Salimbeni Palace and assigned it, in part, to the Salts Customs Office and the Office of Gabella. From 1472, the Monte Pio (Monte di Pietà) was also located there to counter the disgraceful practice of usury. In 1866 the Monte Pio merged into another institution, the Monte dei Paschi (Pascoli), which granted loans by guaranteeing its operations via the annual public incomes of the pascoli di Maremma, controlled by the Sienese state. Since then, by purchasing it, Monte dei Paschi has made it its head office.

Initially on the side of the Ghibellines, they exerted a strong political and economic influence. Owners of castles, palaces towers, they had accumulated wealth especially with the trade of wheat and spices in Maremma. The forerunner was considered a certain Giovanni lived in the thirteenth century, although they liked to say that their lineage descended from a certain Salimbene, who left in 1097 on the First Crusade with a contingent of a thousand Sienese led by Bonifazio Cricci. Also the following year, the legendary Salimbene would go back to conquer Antioch ,of which he would later be appointed patriarch, but he did refuse the office. In 1419, the Sienese Republic confiscated the Salimbeni Palace and assigned it, in part, to the Salts Customs Office and the Office of Gabella. From 1472, the Monte Pio (Monte di Pietà) was also located there to counter the disgraceful practice of usury. In 1866 the Monte Pio merged into another institution, the Monte dei Paschi (Pascoli), which granted loans by guaranteeing its operations via the annual public incomes of the pascoli di Maremma, controlled by the Sienese state. Since then, by purchasing it, Monte dei Paschi has made it its head office.

In the valle dei rozzi (valley of the rozzi)

Via the steep descent that follows the basements of the fortress and the entrance to the former storehouse, you reach via Vallerozzi, whose place name has no definite explanations. Perhaps derived from the name of a family that had property here or, more likely, because it was an area frequented by rough people, as, without many compliments, were defined shepherds who entered from the nearby door not by chance called “sheepfold” to lead their flocks into this area. In Vallerozzi, the painter Giovanni Antonio Bazzi also lived, called Sodom, a great artist, but with an unpredictable character. When he was at Monte Oliveto to Fresco the cloister of the Abbey, the monks nicknamed him “the Mattaccio” precisely because of his continuous mood swings which the friars were subject to. As proof of his bizarre nature, there remains a hilarious letter, sent by him to the Gabella of Siena, where he listed what he owned in “a house in dispute with Niccolò De ‘Libri for his living in Vallerozzi”. This is his tax return: «eight horses; by nickname they are called goats and I am a gelding to govern them; a monkey and a crow that slams and I keep him so he can learn to speak to a theologian donkey in a cage; an owl to scare madmen and a barn owl. Of the locco I will tell you nothing for the monkey upstairs; two peacocks; two dogs, two cats, a tercel, a sparrow, six hens with eighteen pullets. And two Moorish hens and so many birds that it would be confusing to write them all down. Find me three evil beasts, which are three women». Along the road up to the Oratory of the contrada della Lupa and along the side of the church. we reach the square on which Fontebranda rises, one of the most beautiful historical sources of the city. It was built in the fourteenth century according to a project by Camaino Di Crescentino and Sozzo Di Rusticino. With its structure that recalls the Cistercian gothic, with the two large pointed sixth arches, the cruise vaults that cover the interior, it could be called a ‘temple of water’.

Of the locco I will tell you nothing for the monkey upstairs; two peacocks; two dogs, two cats, a tercel, a sparrow, six hens with eighteen pullets. And two Moorish hens and so many birds that it would be confusing to write them all down. Find me three evil beasts, which are three women». Along the road up to the Oratory of the contrada della Lupa and along the side of the church. we reach the square on which Fontebranda rises, one of the most beautiful historical sources of the city. It was built in the fourteenth century according to a project by Camaino Di Crescentino and Sozzo Di Rusticino. With its structure that recalls the Cistercian gothic, with the two large pointed sixth arches, the cruise vaults that cover the interior, it could be called a ‘temple of water’.

Produced by: toscanalibri.it

Texts edited by: Luigi Oliveto

Editorial coordination: Elisa Boniello e Laura Modafferi

Photos: Archivio Comune di Siena

Graphic design: Michela Bracciali