6.3 Siena’s Challenge to the Florentine Renaissance

Pinacoteca Nazionale

This tour focuses on 15th-century Siena, a period that was highly important in the history of the city though it is relatively underappreciated in the realm of tourism, which tends to focus more on the previous centuries. Before visiting the Pinacoteca Nazionale di Siena (National Art Gallery), let’s take a brief detour through the main historical and artistic events of the time in order to better understand the works we will find in the gallery.

The Modern Age is traditionally defined as the historical phase that began in 1492, the year that Columbus discovered America, and continued until the French Revolution in 1789. Artistically speaking, however, the beginning of the ‘new age’—routinely classified under the term ‘Renaissance’—is said to have begun in 1401, the year in which a competition to design the North Door of the Florence Baptistery was announced.

This was a particularly significant event, as some of the most distinguished artists of the time took part, including Lorenzo Ghiberti, Filippo Brunelleschi, Jacopo della Quercia, and Francesco di Valdambrino, the latter two from Siena. The challenge was for each contender to create a bronze panel depicting the Sacrificio d’Isacco (Sacrifice of Isaac). The competition was won by Ghiberti, whose relief panel exhibited traditional features characterized by a Gothic elegance that reflected the prevailing taste of the time, unlike Brunelleschi, who submitted a highly innovative scene, marked by a vibrant dynamism that recalled much more closely the high drama of classical art. Although culturally distant, Siena did not remain impervious to this great artistic and literary revival, as demonstrated by the participation of the two artists mentioned above in the Florentine competition as well as the pioneering desire for advancement on the part of artists such as Stefano di Giovanni, known as il Sassetta, discussed further on.

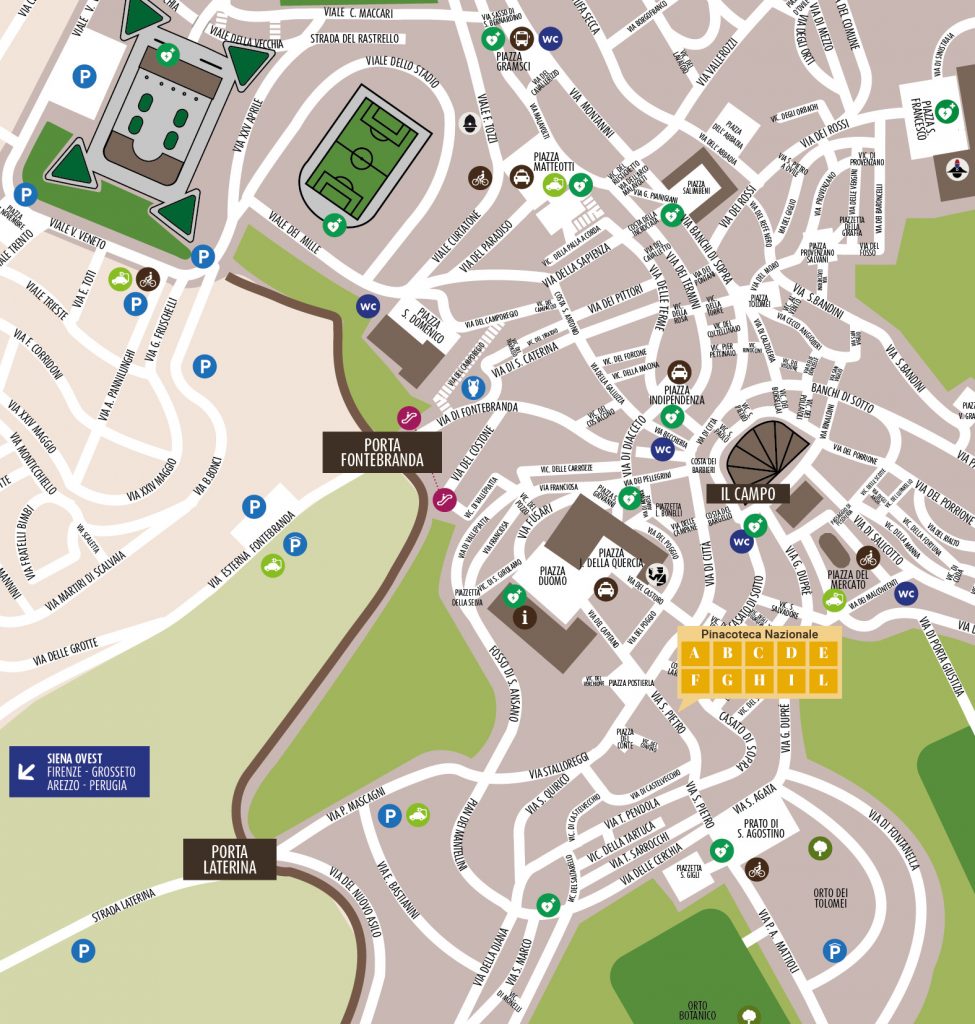

Via San Pietro: entrance

The Pinacoteca Nazionale di Siena houses the most important collection of gold-ground paintings from the 14th and 15th centuries in Siena. The first part of the collection was amassed at the end of the 18th century and initially comprised panels and altarpieces—many of great artistic value—from suppressed convents, lay societies, and dilapidated churches.

In the course of time, the initial collection expanded as works of art were received as donations and bequests, such as those from the former hospital of Santa Maria della Scala and from the Spannocchi-Piccolomini family, who donated many paintings, primarily from the Baroque period.

The museum is housed in the former Buonsignori and Brigidi palaces and was inaugurated in 1932, presenting one of the first chronological layouts in the history of art. Designed by Cesare Brandi, who also published the catalogue in 1933, the initial concept is still largely reflected in the current plan, which is spread over three floors, the first of which houses paintings from the 15th to the 17th centuries, the second the works from the 13th to the 15th centuries, and at the top, the Spannocchi Collection.

The entrance to the museum on via di San Pietro —just a stone’s throw from the cathedral—is not particularly visible, which makes it difficult to imagine that behind the neo-Gothic façade of Palazzo Bonsignori lies a great artistic heritage. A tour of the Pinacoteca gives one the opportunity to trace the evolution of Sienese art from its beginnings in the 13th century with the Maestro di Tressa all the way through to the late 17th century, and to experience important works by the preeminent artists of the 14th century, considered Siena’s ‘golden age’: Duccio di Boninsegna, Simone Martini, and Ambrogio and Pietro Lorenzetti.

Although Sienese art is predominantly valued for its 14th century luminaries, this visit will show that the 15th century was also studded with great personalities who left their mark on the history of the city.

The Second Floor: Paliotto del Salvatore, Maestro di Tressa

Before speaking about the period this tour focuses on, let’s turn our attention to the oldest work in the collection, the first to be seen on the second floor: Maestro di Tressa’s Paliotto del Salvatore (Antependium of the Savior), one of the earliest surviving examples of Sienese art. The painting, executed on wood, once decorated the altar of the church of Santi Salvatore and Alessandro in Castelnuovo Berardenga and depicts Christ the Redeemer as Maiestas Domini (Christ in Majesty) inserted into an ‘oval of light’ symbolising the universal power of God. The figure, hieratic and solemn, is encircled by a tetramorph, an iconographic representation composed of the symbols of the four Evangelists—Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John—in the form of winged animals. To the left of the figure of Christ-God are portrayals of the stories of the Passion of Christ from the New Testament, the Last Supper and the Crucifixion, while on the right are the Storie della Vera Croce (History of the True Cross) derived from the Legenda Aurea (Golden Legend) by Jacopo da Varagine, a work composed in the 13th century.

The Maestro di Tressa, the traditional name given to this painter by critics because of a primitive panel painting coming from the village of the same name, is best known in Siena for another painting which is displayed in the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo di Siena: the Madonna dagli Occhi Grossi (Madonna with Big Eyes), an image before which the citizens of Siena invoked aid and protection on the eve of the Battle of Montaperti in 1260. Leaving the galleries displaying works by the Maestro di Tressa and his contemporaries, one passes through rooms filled with works by Duccio di Buoninsegna and his workshop, followed by paintings from the late 14th century, including the Adorazione dei Magi (Adoration of the Magi), a masterpiece by Bartolo di Fredi.

The Second Floor: Adorazione dei Magi, Bartolo di Fredi

When studying the history of art, one realises that the evolution of fashions and tastes is not compartmentalised; stylistic changes do not occur from one year to the next in a precise and universal manner, nor do they take place in a vacuum, without any influence or inspiration from previous eras. The Sienese school of painting has always stood out for its elegance and refinement, two elements borrowed from the French Gothic style, which the city became acquainted with and made its own thanks to the cultural exchanges that were undoubtedly fostered by the Via Francigena.

The pilgrims and travellers who passed through Siena over the centuries, as well as the flow of goods and craftspeople from beyond the Alps, meant that local artists encountered and assimilated new stylistic elements. They devised a new way of creating designs that was grafted onto the local tradition, characterised at the time by Byzantine schematism and hieratic imagery; such syncretism is clearly evident in the 13th and 14th century works by artists such as Duccio di Buoninsegna, Simone Martini, and Pietro and Ambrogio Lorenzetti.

This copresence of different tastes and manners was mentioned earlier, when, referring to the competition to design the North Door of the Florence Baptistery, the aesthetic conflict that led the ‘innovative’ Brunelleschi to lose the competition to the ‘traditional’ Ghiberti was recounted.

Lorenzo’s art was rather anchored in a sophisticated Gothic manner, a style known by the conventional term International Gothic. The echoes of this style were long-lived, so much so that in 1423, as many as 22 years after the notorious competition, the famous painter Gentile da Fabriano painted an Adorazione dei Magi (Adoration of the Magi) for the powerful Florentine merchant Palla Strozzi for his chapel in Santa Trinita. The style of the triptych is ‘courtly’ and the depicted characters are opulently dressed, as befitted members of the noble houses, to which the Magi indeed belonged. Before the Florentine commission, Gentile had travelled to other Tuscan cities, and, as it is known that he stopped in Siena, it is intriguing to think that the artist took inspiration for his future work from this painting of the same subject by Bartolo di Fredi, completed in 1385.

In fact, the Sienese painter’s work fully reveals the narrative and naturalistic characteristics of the late Gothic period: the background is divided between the moment before the Adoration itself, i.e. the arrival of the Magi in Jerusalem, and the next phase, when the three kings leave for their homeland, once again following the light of the star. The city depicted in the background seems to have all the features of Siena—recalling the images painted by Ambrogio Lorenzetti in the Sala della Pace in the Palazzo Pubblico in the middle of the previous century—and provides an accurate documentation of how the city, turreted and plastered, must have looked in the 14th and 15th centuries.

Another delightful particular in the work is the symbolism in the representations, one being the three Magi in the foreground, depicted according to the three ages of humans. The first figure is blond with a youthful face, the second, wearing a yellow cape, is middle-aged with darker hair, and the third is an old man with grey hair and a long beard. It is no coincidence that the latter kneels directly before Jesus, as it is the elder’s wisdom which makes him certain that he is gazing upon the incarnation of God.

The opulence of detail found in late Gothic painting—from the rich garments to the jewellery and even the hairstyles—was also reflected in sculpture and architecture: just think of the great Nordic cathedrals or the floral ornamentation on the Milan cathedral.

Madonna dell’Umiltà, Giovanni di Paolo

As we move on to the 15th century, the first work we should focus on is Giovanni di Paolo’s Madonna dell’Umiltà (Madonna of Humility).Although this work dates from the 1430s, a period in which Masaccio had already left his revolutionary and indelible mark on the Florentine environment, it demonstrates how Siena remained proudly anchored in Gothic tradition. The work is called Madonna dell’Umiltà due to its depiction of the Virgin Mary cradling her child while seated on the grass of a field rather than on a traditional throne as befits divine subjects. The rather sinuous line of the slender bodies reminds us of the figures from the Duccesque tradition. The background features a bird’s eye view of mountains and turreted cities, while around the figure of the Virgin a garden flourishes—perhaps a reference to the hortus conclusus (enclosed garden)—its variety of plants and fine details revealing a careful study of botany.

The background features a bird’s eye view of mountains and turreted cities, while around the figure of the Virgin a garden flourishes—perhaps a reference to the hortus conclusus (enclosed garden)—its variety of plants and fine details revealing a careful study of botany.

Also by Giovanni di Paolo, dating back to the 1440s, is a replica of the Sienese painting which now resides in the Museum of Fine Arts Boston in Boston, Massachusetts.

Polittico dell’Arte della Lana, F Sassetta

While in general the Sienese School of the 15th century remained linked to the pictorial tradition of the previous century, there was one artist who was no stranger to the innovations coming from the Florence of Donatello and Masaccio: Stefano di Giovanni, known as il Sassetta. His first documented work, dated 1423 and on display in different parts of the Pinacoteca, is the Polittico dell’Arte della Lana (Wool Merchants’ Guild Altarpiece).

Unfortunately, many of the panels have been lost while others are housed in museums around the world. Of those in the Pinacoteca, the Ultima Cena (the Last Supper) is undoubtedly one of the most beautiful. In the scene of Sant’Antonio Colpito dai Demoni (St Anthony Tormented by Demons), it is clear that il Sassetta incorporated his studies of Florentine Renaissance developments: the scene’s perspective was a new feature compared to the works of his contemporaries; the attention to the naturalistic component, as evidenced by the skies rendered with white streaks, is also noteworthy.

Another characteristic that distinguishes the artist from his peers is his attention to the anatomical and physiognomic details, as can be seen in the depiction of the saint’s skull being thrown to the ground by the demons circling around him and beating him with clubs.

The work dating from the artist’s later phase is not nearly as innovative, a change of course perhaps due to the need to satisfy the tastes of his clients, who were still tied to the stylistic features of the previous century. Il Sassetta’s life abruptly came to an end in 1450, probably due to pneumonia contracted while he was working on the fresco of the Incoronazione della Vergine (Coronation of the Virgin) on the Porta Romana—one of the gates of the city walls— a work that was completed by his pupil Sano di Pietro. Il Sassetta was also the teacher of Giovanni di Paolo, Vecchietta, and his own son Giovanni di Stefano.

Annunciazione, Jacopo della Quercia

Next is the Annunciazione (Annunciation), a sculptural piece by Jacopo della Quercia consisting of two statues executed in wood and then painted: the Announcing Angel and the Virgin Annunciate. It is common in Sienese churches to find these two figures on either side of the altar, a compositional arrangement that highlights the fruit of their meeting, Christ, being celebrated on the altar. It is quite evident that Jacopo della Quercia’s sculptures are still linked to the prevailing trend of the previous century, both for the slender contrapposto form and for the rich tangle of draped cloth, the latter a constant element in the art of the Sienese sculptor, influenced by the Gothic art of the 14th century.

Madonna in trono con Santi, Vecchietta

Painted in the last years of his life for his own mortuary chapel, which Santa Maria della Scala had granted him inside the Church of Santissima Annunziata, the work was to be accompanied by the bronze Cristo Risorto (Christ Resurrected), which was eventually placed above the high altar of the same church. Nothing more is known about the burial of the artist as there is no trace of him in the church.

The painting depicts Peter and Paul, the institutional saints, together with St Francis and St Lawrence. Although the altarpiece is badly damaged, it can still be appreciated for the way the figures are arranged in a semicircular box with perfect perspective, in which the wooden coffers of the ceiling, together with the angels emerging as if from two small windows behind the throne, emphasise the sense of depth of the ensemble. The figures are rendered in a sculptural manner, even if they are not imposing; the clothes are lustrous, almost iridescent, producing an effect of wet cloth as in classical statuary.

La Natività di Francesco di I Giorgio Martini

Together with Giovanni di Paolo, Sano di Pietro, and Matteo di Giovanni, Vecchietta is one of the artists who created the five altarpieces in the Pienza Cathedral, the only examples of the Sienese School in the ‘time of humanism’ promoted by Pope Pius II. Heir to that extraordinary humanist experience, as drafted in a treatise by the great scholar Leon Battista Alberti, was another artist hailing from Siena: Francesco di Giorgio Martini. A pupil of Vecchietta, Francesco left a significant legacy in the field of architecture, both as a designer and as a draughtsman; he was so highly regarded as an architect that, as Florence did in its time with its Giotto, the Republic of Siena tried hold on to him when the Italian courts sought him for his talent as a civil and military architect (he worked at length in Urbino, for Duke Federico da Monte Feltro, as well as in Jesi and Ancona).

Francesco was also a prolific painter, as can be seen by the series of works he produced which are on display in the Pinacoteca. Although the quality of the paintings is not on the same level as his sculptures or drawings—most likely due to the fact that the master left most of the practical work to his workshop assistants—some excellent works exist, many of which can be found in this gallery, including the Natività con San Bernardino e San Tommaso d’Aquino (Nativity with St Bernardine and St Thomas Aquinas), a Madonna con Bambino e Angelo (Madonna and Child with Angel), and the beautiful Incoronazione della Vergine (Coronation of the Virgin).

In the Natività, it is possible to appreciate details that denote the study and interest shown by Francesco towards the Florentine plasticity tradition, where artists such as the Pollaiolo brothers and Andrea del Verrocchio revisited the Gothic influences of Luca della Robbia but with a completely new interpretation; in the Siena altarpiece, one can notice refined details such as the elegant head of the Virgin, or the vibrant folds of the mantle.

L’Incoronazione della Vergine, L Francesco di Giorgio Martini

In the Incoronazione della Vergine (Coronation of the Virgin), the artist synthesises, in the most felicitous way possible, the manner of the two rival schools of art, those of Siena and Florence, combining Florentine plasticity and sense of space with the attention to ornamentation and sinuosity typical of Sienese tradition. The saints and angels attending the event are symmetrically arranged on either side, almost becoming the supporting structures of the circular disc on which Christ and the Virgin rest.

In short, Francesco di Giorgio was truly an extraordinary artist, mistakenly underappreciated in the popular works of Italian art history. Another artist present in the Pinacoteca is Neroccio di Bartolomeo de’ Landi, a multifaceted personality like Francesco di Giorgio— and whose pupil and collaborator he was—but still bound to the preference for refined elegance of the previous generation. He produced several paintings of the Madonna with Child and Saints, the features of whom reflect those previously drawn by his master. Neroccio distinguished himself above all as a sculptor: his masterpiece is the wooden statue of St Catherine of Siena, made for the Oratory of the Contrada dell’Oca. The last rooms of the Pinacoteca dedicated to 15th century art contain numerous altarpieces, most depicting the Virgin between saints, by Sano di Pietro, a pupil of il Sassetta. Following a youthful phase characterised by a certain creative verve, as is perhaps confirmed by his homonymy with the ‘Master of Observance’, Sano di Pietro decidedly changed his style of painting in his later years, when he became mechanical and repetitive, displaying few new ideas except in his small-format works.

This is the end of our journey through the Pinacoteca Nazionale di Siena. Please don’t leave the museum without first admiring the Sienese works from the 16th and 17th centuries on the first floor.

Text by Ambra Sargentoni (Ambra Tour Guide) Editorial coordination: Elisa Boniello and

Laura Modafferi

Photos: Archivio Comune di Siena, Leonardo Castelli, Archivio Pinacoteca Nazionale di Siena, with the permission of the Ministero della Cultura, Direzione Regionale Musei della Toscana

Graphics: Michela Bracciali